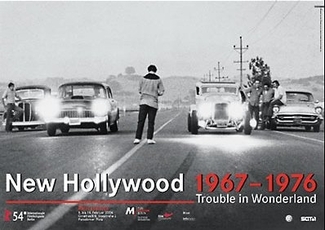

The New Hollywood era, also known as the American New Wave, the Hollywood Renaissance, and the auteur period, is when the Swinging '60s arrived in Hollywood. Lasting from approximately 1965 to 1983 (though different sources give different estimates, with one such example being pictured above), it was marked by the rise of a new generation of young, film-school-educated, countercultural filmmakers — directors, actors and writers alike — whom Hollywood felt could speak to the new generation of young people in ways that their older stars could not. By this point in time, Hollywood was desperate to hold onto any remaining scrap of relevance in an era that saw its dominance of American pop culture pulverized by the trifecta of television grabbing its mass audience, foreign cinema by masters like Akira Kurosawa, Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman, and François Truffaut eroding its critical respectability, and independent films such as those produced by John Cassavetes and Roger Corman sucking up young talent. Driven by a combination of both mercantile interests (keeping pace with the changing tastes of the moviegoing public) and genuine enthusiasm to depict stories and elements never before seen in American cinema, the studios opened the doors like never before. Aspiring filmmakers who had graduated from film school and made one or two movies could now shop their big ideas to the studios and receive total Auteur License of the kind that Orson Welles had received for Citizen Kane. The result was a decade or so of bold experimentation, perhaps the greatest creative explosion in mainstream American cinema.

The rise of the New Golden Age...

While the exact starting point of this era is a matter of contention, with Wikipedia repeatedly shifting the starting point on its list![]() back and forth (the earliest entry on the list as of this writing is 1965's Mickey One), Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider, released in 1967 and 1969 respectively, are cited by the widest variety of sources as the first New Hollywood films. They were made by big studios (Warner Bros. and Columbia Pictures, respectively) and featured several of their hot young stars, and yet they had violence, sexuality, and a dark tone that owed more to European cinema than anything homegrown. However, these films were, in many ways, the culmination of a larger trend in American cinema, stemming from the collapse of The Hays Code. The Code had already lost its primary reason for being around in 1952/1953 when the US Supreme Court declared film (and to an extent entertainment) to be a protected art form under the First Amendment (and even its authority to allow the release of films thanks to the 1948 landmark Paramount Decision), but by the late '50s, such filmmakers as Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, Elia Kazan, Stanley Kubrick, Douglas Sirk, and John Cassavetes, and even foreign filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock and Sergio Leone, were already breaking down the Code and putting in challenging content, most of which were critically hailed. At first, the main enforcer of the Code, the Hays Office, had tried to demand the censorship of those films, but their attempts backfired and made the Code look even more ridiculous. Then the Hays Office tried to save face by claiming those films were "special exceptions" such as The Pawnbroker (with its short scene of plot-relevant nudity) and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (with its equally plot-relevant harsh language). However, no-one was buying it and soon, opinion of the Code changed and the general public (as well as the Catholic and Protestant Churches, who were the main backers of the Code) stopped supporting it. During this time, the big studios, who's support of the Code had also ended, started disturbing those films as well as similar films without the Hays Office's seal of approval (which they could do thanks to the Paramount Decision. For more about it, read Fall of the Studio System) in direct defiance, thus further reducing the Code's authority. Then, in 1965, the Supreme Court banned any censorship and/or banning of any films in America with the landmark Freedman v. Maryland decision, finally putting the antiquated censorship code out of its misery. Finally in 1966, major studio MGM produced and released Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup, which featured explicit nudity, as a final act of defiance against the Code and the Hays Office (who had refused to give their seal of approval prior to Freedman v. Maryland) and it became a critical and box office smash hit. Thus, the Hays Office, as well as the Protestant Film Office (who had also championed the Code), closed their doors soon after.

back and forth (the earliest entry on the list as of this writing is 1965's Mickey One), Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider, released in 1967 and 1969 respectively, are cited by the widest variety of sources as the first New Hollywood films. They were made by big studios (Warner Bros. and Columbia Pictures, respectively) and featured several of their hot young stars, and yet they had violence, sexuality, and a dark tone that owed more to European cinema than anything homegrown. However, these films were, in many ways, the culmination of a larger trend in American cinema, stemming from the collapse of The Hays Code. The Code had already lost its primary reason for being around in 1952/1953 when the US Supreme Court declared film (and to an extent entertainment) to be a protected art form under the First Amendment (and even its authority to allow the release of films thanks to the 1948 landmark Paramount Decision), but by the late '50s, such filmmakers as Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, Elia Kazan, Stanley Kubrick, Douglas Sirk, and John Cassavetes, and even foreign filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock and Sergio Leone, were already breaking down the Code and putting in challenging content, most of which were critically hailed. At first, the main enforcer of the Code, the Hays Office, had tried to demand the censorship of those films, but their attempts backfired and made the Code look even more ridiculous. Then the Hays Office tried to save face by claiming those films were "special exceptions" such as The Pawnbroker (with its short scene of plot-relevant nudity) and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (with its equally plot-relevant harsh language). However, no-one was buying it and soon, opinion of the Code changed and the general public (as well as the Catholic and Protestant Churches, who were the main backers of the Code) stopped supporting it. During this time, the big studios, who's support of the Code had also ended, started disturbing those films as well as similar films without the Hays Office's seal of approval (which they could do thanks to the Paramount Decision. For more about it, read Fall of the Studio System) in direct defiance, thus further reducing the Code's authority. Then, in 1965, the Supreme Court banned any censorship and/or banning of any films in America with the landmark Freedman v. Maryland decision, finally putting the antiquated censorship code out of its misery. Finally in 1966, major studio MGM produced and released Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup, which featured explicit nudity, as a final act of defiance against the Code and the Hays Office (who had refused to give their seal of approval prior to Freedman v. Maryland) and it became a critical and box office smash hit. Thus, the Hays Office, as well as the Protestant Film Office (who had also championed the Code), closed their doors soon after.

This opened the floodgates for the era of permissiveness that would typify film-making for the rest of The '60s and into The '70s, with a new ratings system being formed in 1966 and finally enacted in 1968 by the new boss of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), Jack Valenti. Unlike the Hays Code, which only allowed sorta-edgy content that would probably qualify for a PG (or a very light PG-13) today, the MPAA's rating system recognized the space in the public sphere for films for an adult audience, creating a compromise between anti-censorship artists and Moral Guardians by establishing four tiers for films: "G" for family-friendly films, "M" for films with potentially disturbing subject matter that were still determined to be all-ages appropriate, "R" for films that were deemed objectionable for children to view by themselves, and "X" for explicit and potentially offensive movies.note The new freedom afforded by the MPAA's ratings system encouraged studios to sponsor and accept bold and radical new content. Films like Bonnie and Clyde, Rosemary's Baby, The Graduate, Midnight Cowboy, Cool Hand Luke, The Producers, and Easy Rider broke countless taboos, earning immense critical acclaim and, more often than not, box office returns in the process, proving that both the Hays Code and the Golden Age were dead.

Realism and immersion were major themes in such movies, a backlash against the spectacle and artificiality that defined the studio system. A symbol of this emphasis on realism was the choice of many filmmakers to shoot on location— not only was this now far less expensive than shooting on set due to advances in technology, it also heightened the feeling that the people on screen were in a real place. In addition, such films were infused with sexuality, graphic violence, drugs, rock music, anti heroes, anti-establishment themes, and other symbols of the '60s counterculture that would've been unthinkable in mainstream American cinema just a few years earlier. Many New Hollywood filmmakers openly admitted to using marijuana and psychedelic drugs, furthering their popularity in the general climate of the '60s. In addition, the rigid cliche of the WASP-y, white-bread all-American movie star was challenged with the rise of actors who forced the parameters open, like the suave, intelligent black man Sidney Poitier, exotic European sex symbols like Brigitte Bardot and Sophia Loren, the awkward but lovable Jews Dustin Hoffman, Woody Allen, and Richard Dreyfuss, Italian-American antiheroes Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, and the hardbody heartthrob Asian tough guy Bruce Lee. These and other actors hit it big in part by being seemingly nothing like any major movie star before.

The success of New Hollywood's early films stood in sharp contrast to the colossal, studio-busting failures of the last stretch of Old Hollywood-style filmmaking — in particular, the many money-losing, big-budget, mostly family-friendly musicals (such as Doctor Dolittle, Camelot, and Hello, Dolly!) made in the wake of the 1965 smash The Sound of Music. This caused the studios to grant almost complete creative control to these upstart filmmakers. As The '70s rolled in, such films as Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather, Sidney Lumet's Dog Day Afternoon and Network, Roman Polański's neo-Noir Chinatown, Michael Cimino's The Deer Hunter, and Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver were released to not only near-universal critical acclaim, but also massive ticket sales, earning their studios boatloads of cash in the process. For a while, it appeared that this strategy was paying off big time. On top of all that, cinema was finally taken seriously from an artistic point of view. With TV becoming the dominant mass medium, the cultural scorn heaped on it changed the image of film by comparison. Whereas cinema was previously considered a low-class medium, now it became "quality entertainment" with an artistic respectability nearly on a par with other arts like live theater. (Compare it to the situation today, where cable and streaming television is itself becoming "respectable" while video games and webshows are often labeled as "low-brow" and network TV is struggling to stay relevant, as well as the way popular music was taken more seriously by critics in the wake of The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.) For a time, it looked as if the worst was over, and it seemed like Hollywood was finally out of its post-war slump.

...and the fall.

Alas, these good times were not to last. For one thing, while some of these films were huge hits, average weekly attendance plummeted from roughly 45 million per week in 1965 to roughly 19 million in 1969. While some of this can be attributed to the continued collapse of the studio system, the numbers only crept back up into the 20-25 million per week range for the next decade, staying there and never recovering to old heights. TV was here to stay, and film would never again enjoy the dominance it once had in the broader American entertainment industry.Furthermore, towards the end of the '70s, the New Hollywood film-makers who had originally burst on the scene to make low-budget adult alternatives to The '60s Epic Movie started making films with bigger budgets and moving towards riskier ventures. In the case of Apocalypse Now, the risk paid off; the film won several awards and was a box-office success despite its notoriously Troubled Production, chronicled by several tabloids and gossip mongers, leading many to predict a Cleopatra-sized catastrophe in the making. Formerly, Hollywood film-makers would court this publicity, but the mood had shifted by this point. While earlier, such artistic fastidiousness was praised as an example of uncompromising artistic commitment, the story that was now spun was that of over-reaching and spoiled film-makers who were abusing their privileges. Michael Cimino's notorious 1980 flop Heaven's Gate became the rallying point for this mentality. At the end of it all, United Artists (the studio behind Heaven's Gate) had gone bankrupt and had been sold to MGM, and The '80s was a time when directors, even economical ones, struggled to make ambitious films in a market driven towards family fare.

1977 was the year when the shift from New Hollywood to The Blockbuster Age of Hollywood kicked into high gear, with two films made on modest budgets with no "big stars" in particular heralding the transition. Rocky, which debuted at the end of 1976 and dominated the box office throughout early 1977, starts out very New Hollywood, as a gritty urban drama centered on a seeming Antihero, but eventually transitions into a inspirational underdog tale. The rapturous response from critics, audiences, and ultimately Hollywood itself (with its Academy Award for Best Picture) showed that there was still a market for old-fashioned crowd-pleasing. Then Star Wars, a Space Opera that was about as far removed from realism as could be, made at considerable risk (described by Roger Corman, The Mentor of the group, as a B-Movie during production), became an immensely profitable smash hit. Directors at the time like Martin Scorsese and John Milius, and in 2015, George Lucas himself, noted that its success taught new investors the wrong lessons, causing many to believe that the success of the film lay in its ability to spin off merchandise rather than its own merits as a film.

With high-profile bombs discrediting the auteurs, Hollywood turned away from their sorts of adult films and towards making films for the whole family, which led to several imitations and the drying up of funds for many of those filmmakers, ironically erasing the context which led to Star Wars being made in the first place. Directors like Woody Allen argued that, despite the occasional flop, by and large these films made a profit and were misblamed for changes the industry was going through anyway. Scorsese has described the period as being, more accurately, the space between the old and the new, where the next generation of blockbusters were once again in control of the situation, and the The Blockbuster Age of Hollywood was underway. Somewhat tellingly, the New Hollywood ethos still persisted for a brief period of time during the early days of the Blockbuster Age, with Francis Ford Coppola's 1983 film Rumble Fish being more or less the last film of the former era, and the idea that directors deserved just as much say in the artistic product as— if not more than— studio executives would become a mainstay well into the Blockbuster Age.

The first buyouts of studios by outside forces began during this time, as corporations not only saw that Hollywood was big business, but that, in their currently troubled state, the studios were ripe for hostile takeover.

If you want blood... you've got it!

The auteur filmmaking of New Hollywood is popularly understood as a phenomenon chiefly relegated to the major studios, institutions that could afford to finance the production of these blockbusters. For those who couldn't make it in Hollywood... well, the Hays Code was gone, the Moral Guardians were neutered, and moviegoers were demanding much edgier and more graphic content, so you can guess what happened. The above-described "auteur period" is only one of the two phenomena associated with filmmaking in the 1970s; the other, as Quentin Tarantino and his ilk have so masterfully taught us, was the explosion of B-grade exploitation films. Whole new sub-genres abounded in American cinema, from "blaxploitation" targeted at newly-empowered (but still largely ignored by Hollywood) African Americans in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, to wild martial arts and Wuxia action films imported from Hong Kong, with Bruce Lee becoming a cinematic legend with only a handful of films. Famed low-budget filmmaker Roger Corman— who mentored many of the big talents of the auteur period— spent the prior decade developing a sweeping body of work famous for the frugality of its production, and continued to produce films even after he stopped directing in 1971.The American horror genre entered a new golden age of creativity. On the Hollywood side of the genre, such films as Rosemary's Baby, The Omen, The Exorcist, and Carrie all worked hard to restore the artistic respectability of the genre, winning critical acclaim that few horror films have achieved since. Meanwhile, on the indie side, blood-drenched flicks like Night of the Living Dead (1968) and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) shocked viewers with their brutality. Italian cinema played a major role in the growth of the genre, with such visionaries as Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci and Mario Bava all heavily influencing the direction that the horror genre would take well into the '80s.

In conclusion

While the New Hollywood era lasted just under two decades compared to the several decades of the Studio System and Blockbuster eras, it had a profound impact on how Hollywood operated. New Hollywood was the era in which, at least in the eyes of academics and the American cultural elite, cinema finally secured its status as True Art after decades of fighting for acceptance alongside literature, theater, and music. The old studio system, in which the producers had the ultimate say in everything that happened on set and backstage, was gone for good, and wouldn't be replicated even after they started reasserting their power.

From the perspective of directors, the era was more or less a Full-Circle Revolution. In the end, the studios pushed back against the excesses of "visionaries" and Executive Meddling returned to prominence— assuming, of course, that directors managed to get their script and idea approved to start with. For all the creative freedom directors had on some productions, they were never quite able to take it all the way and create a long-standing form of institutional support. The likes of Peter Bogdanovich, Francis Ford Coppola, and William Friedkin had earlier tried to form a joint co-operative venture where by they would produce each other's films (similar to a plan hatched by William Wyler and Frank Capra in The '40s), but this failed because of a clash of egos, disproportionate incomes, and inability to absorb costs. Italian auteur Bernardo Bertolucci, a huge influence on this generation (and whose 1900 was partly funded by American studios) noted that American filmmakers of this era never quite managed to achieve anything![]() like the legislative success in France, where directors managed to gain copyright on their works, and remained more or less under the thumb of the studios and had no ground for themselves when the era was over.

like the legislative success in France, where directors managed to gain copyright on their works, and remained more or less under the thumb of the studios and had no ground for themselves when the era was over.

The most significant gain for directors creators rights wasn't achieved by any of the young stars of this period but by Robert Aldrich, a remnant of the studio system who as president of the DGA in The '70s negotiated for better pay, greater rights, and the first cut privilege which remained in effect later on. The so called Director's Cut that became all the rage from The '80s onwards is in part a result of Aldrich's insistence that directors get to make their own version before studios and other hands have their feedback via previews or additional screeningnote . The only '70s creator who actually tried to extend these gains was George Lucas, who in The '80s tried to argue to Congress for creator's rights and control over projects to be recognized legally, but it never caught traction or backing from others, or much notice in the media.

Still, the influence and cultural prestige of films from this era was such that Hollywood did entertain, if far less than usual, the idea of movies made for the art. Certain filmmakers who emerged from the era with their careers intact, like Woody Allen, Clint Eastwood, Steven Spielberg, and much later, Martin Scorsese (after a difficult period in The '80s), managed to carve niches within the industry and remained solvent, setting a precedent for the likes of The Coen Brothers, Spike Lee, Wes Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, Edgar Wright, David Fincher, and Steven Soderbergh, who later became prominent as creative filmmakers within the mainstream.

The output of the era, like that of the Golden Age, is often put through the Nostalgia Filter, with some saying that the 1970s was the last truly classic decade for American cinema (expect![]() Critical Backlash and Flame War for those who disagree). At the end of the day, the lessons learned from New Hollywood, both good and bad, would be put to use by the studios— and their new corporate owners— to start The Blockbuster Age of Hollywood, the true new Hollywood establishment.

Critical Backlash and Flame War for those who disagree). At the end of the day, the lessons learned from New Hollywood, both good and bad, would be put to use by the studios— and their new corporate owners— to start The Blockbuster Age of Hollywood, the true new Hollywood establishment.

Tropes from this Era

- Anti-Hero: Types II-Types IV generally speaking. It wasn't until Luke Skywalker, Superman and Rocky (to an extent), that you had classic-style heroes showing up again, albeit as Reconstruction.

- Attention Deficit Creator Disorder: The most prolific of this period was Robert Altman, who made fifteen films between 1970-1980. He dropped down to 7 movies in The '80s at which point he had moved abroad to France and worked on TV. A indicator on how the industry changed. Other prolific film-makers of this time include Sam Peckinpah (who made a film a year between 1969-1975).

- The Bad Guy Wins: Directors of this era delighted in rewarding villains and subverting cliches, after decades of studio-mandated censorship. Special examples include Chinatown, The Parallax View, Heaven's Gate, Mean Streets, and The Godfather.

- Christianity is Catholic:

- Several of the key directors from this group were either raised Catholic (Coppola, Scorsese, Altman, Cimino) or grew up in a Catholic environment (De Palma, who was actually a baptized Presbyterian). As a result, themes of Catholic guilt and the conflict between the traditional mores of the church versus modern life show up a lot, most notably in The Godfather, The Conversation, Mean Streets.

- Likewise much of the Religious Horror was Catholic-centric, even when the directors in question were Jewish as in the case of Rosemary's Baby and The Exorcist.

- Darker and Edgier: For many this was the darkest era in American cinema. Films were bleaker, pessimistic, featured more violence and edgy content than any other period of mainstream film-making. To put this in perspective, films like Straw Dogs (1971) and Nashville were released by major studios and indeed, Jack Nicholson noted that Robert Towne's original ending for Chinatown sounded interesting to him because it went against the ongoing trend for Downer Ending in this time.

- Deliberately Monochrome: This was the first decade where color cinema became the norm (The '60s being a period of transition) and where use of black-and-white became an "artistic choice". Notable examples include The Last Picture Show, Paper Moon, The Honeymoon Killers, Lenny, Manhattan, Eraserhead, Young Frankenstein, Raging Bull.

- Genre Deconstruction: Almost no genre was left untouched.

- Film Noir: Neo-noir like Chinatown and The Long Goodbye put all the subtext of the classic noir on the surface for everyone to see while critiquing the archetypes of the Private Detective and Femme Fatale.

- Epic Movie: This was the hope of such films as Heaven's Gate. Likewise, the genre evolved by being blended into new ones. The Godfather for instance was more of a Hollywood epic than it was a gangster film.

- The Musical: Audiences had a tougher time accepting the revisionism of classic musicals, and indeed attempts to do so, such as At Long Last Love and New York, New York became proverbial flops by the end of the decade. The fact that this was an era where rock music started being used as accompaniment in many films, also contributed to the decline of the traditional musical. Cabaret notably made all the songs in-universe performances and the dissonance between the singing and the horror of Nazi Germany was used to illustrate the characters denying what's really going on around them. The other possible exception is The Rocky Horror Picture Show; "possible" because it is at least as much a Genre Mashup as a deconstruction, it was a stage musical that used rock at least as much as traditional show tunes, and it only found its audience as a midnight-screening Cult Classic.

- Romantic Comedy: Films by Woody Allen, especially Annie Hall, but also Sydney Pollack's The Way We Were showed how difficult relationships were, and what love meant in a time of no-fault divorce and blended marriages.

- The Western: Sam Peckinpah's films tackled the New Old West. Other films from this time also used the Western to cast a dim view on American history, while Robert Altman's McCabe & Mrs. Miller showed how the West really looked like.

- Genre-Busting: Robert Altman essentially invented perhaps the most unique genre from this period, the Ensemble Movie

- Genre Throwback: The era began when American film-makers revolted against the old Hollywood genres by making stories relevant to The '70s. It ended when the same film-makers fell into a phase of nostalgia for the old genres from their childhood and sought to revive and update it for The '70s. In most cases it failed. The one success was Star Wars. The main reason for the latter's success is that fundamentally, New Hollywood still structured its ideas of genre and its codes on Old Hollywood, i.e. The Western, The Musical, the Epic Movie, Film Noir and they were more or less providing Deconstruction whereas Lucas was doing the novel idea of taking the most disreputable and forgotten products of the studio era (The B-Movie serial films of Flash Gordon and others) and providing it scale, seriousness and polish that they never had before.

- Gorn: For the first time, really shocking bloody violence became part of mainstream filmsnote . Trailblazing examples include: Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Bunch, A Clockwork Orange, Dirty Harry, The Godfather, The Long Goodbye, Taxi Driver. This led to much debate (at the time and afterwards) about "glorifiying violence". Of course, some of these examples have been surpassed by later films to the point they seem a little tame in retrospect; but at the time, most were considered very disturbing and offensive.

- Hotter and Sexier: This was a period where nudity became permissible on American screens and sex scenes became more and more common. Indeed some actresses who had been around beforehand went nude in film. Deborah Kerr was one such actress who went topless in The Gypsy Moths to compete with younger actresses who were willing to show more skin.

- Male Gaze: This period led to the trope being named in Laura Mulvey's now infamous essay on the subject; films from the late 60s and 70s shamelessly ogled women's breasts, legs and other body parts to showcase their beauty in ways not done in the Golden Age. The trope's logic has however since been disputed by some third wave feminists (most notably Liana K), who point out that 'Male Gaze' automatically assumes that every male would be attracted to the same thing. In her series A Gamer's Guide to Feminism

, she points out that the name came about in a time when homosexuality was still considered a mental illness. The trope was coined in specific response to the New Hollywood Era's depictions of women.

, she points out that the name came about in a time when homosexuality was still considered a mental illness. The trope was coined in specific response to the New Hollywood Era's depictions of women.

- One Degree of Separation:

- George Lucas is the linchpin of the New Hollywood era, being one or two degrees away from Coppola (starting as his apprentice and co-producing many movies together), Spielberg (collaborating on Indiana Jones), Scorsese (via Marcia Lucas who edited Taxi Driver), De Palma (who suggested a modification for the title crawl of Star Wars), Milius (collaborator on the first drafts for Apocalypse Now which was originally going to be his project), Schrader (producing Mishima). When Martin Scorsese was nominated for Best Director on The Departed, Lucas presented along with Coppola and Spielberg (which was itself a tell on who was going to win), and it turned into an impromptu roast on Lucas still not winning any oscars among their generation.

- Producer Julia Phillips along with her husband Michael worked on classics like The Sting, Taxi Driver, Close Encounters of the Third Kind. She was the first female producer to win an Oscar, and while she has a somewhat mixed reputation as with most producers (some like her, others don't), she was in many ways the main connective tissue of the era. Her house was the meeting ground for many of the talented names of this era (Spielberg, DePalma, Schrader, DeNiro and others) and was the place where for instance Scorsese met Schrader, and likewise one of the few spots that the so called young Turks actually got together to hang out and talk shop.

- Roger Corman, meanwhile, produced early directing work by Coppola, Scorsese, and Bogdanovich, not to mention performances by Jack Nicholson, Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda and Robert De Niro.

- Oscar Bait: Averted. The Seventies saw some of the most varied

(in genre and storytelling) and non-traditional genres getting nominated and winning. Much of these films were also drastically different in style from earlier films, in terms of use of camera, narration and storytelling gimmicks.

(in genre and storytelling) and non-traditional genres getting nominated and winning. Much of these films were also drastically different in style from earlier films, in terms of use of camera, narration and storytelling gimmicks.

- This includes disaster films (The Towering Inferno), horror films (The Exorcist), Black Comedy (M*A*S*H), science-fiction (A New Hope) getting nominated. Likewise it was during this decade that crime movies finally started becoming prestigious and getting nominations and winning (Midnight Cowboy, The French Connection, The Godfather, The Sting, The Godfather II). After the Seventies, only two other crime movies would win Best Picture, The Silence of the Lambs and The Departed. Likewise, Annie Hall became one of the few movies to break the comedy ghetto.

- More generally, previous decades Oscar winners had to be uplifting and glorifying even when depicting scenes from history or especially if they depicted war. This changed in The '70s, the winner at the start of the decade was a Biopic like Patton that portrayed a man who believed that War Is Glorious and the winner at the end of the decade was The Deer Hunter which was about the psychological problems caused by the war.

- Of course in certain ways, the Academy redefined the "new normal" with sentimental portrayals of mental illness (One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest), Real Is Brown working-class dramas like Rocky and kitchen-sink melodrama like Kramer vs. Kramer becoming templates for oscar bait for the next four decades.

- Outlaw Couple: A very popular trope, made and codified by Bonnie and Clyde. Low-budget takes include The Honeymoon Killers (a very seedy low-budget look at it) and Wanda (by Barbara Loden). Other notable examples include, Badlands (by Terrence Malick) and Thieves Like Us (by Robert Altman), and Steven Spielberg's first feature, The Sugarland Express

- Pop-Star Composer: The movies followed the golden age of rock music and The British Invasion and made much of actual songs to score the films, often for montage sequences and often as Suspiciously Apropos Music. Easy Rider more or less paved the way for other films to follow (such as Robert Altman's McCabe & Mrs. Miller which is entirely scored by three Leonard Cohen songs) and Mean Streets.

- The Remnant:

- It was called "New Hollywood" but a few old-timers were still around making films. For instance, Billy Wilder made Fedora and Avanti!, Otto Preminger made his final films in the same decade, as did George Cukor. Alfred Hitchcock is especially notable for being the rare classic director who actually tried to update with the end of censorship (evident in the greater sex and violence of Frenzy and the more diverse international cast of Topaz while Family Plot (his last film) uses three actors from Robert Altman's Production Posse). Likewise, Elia Kazan's final films, The Arrangment and The Visitors featured Faye Dunaway and James Woods, and the former film had a frenetic and experimental editing style that was all the rage, while The Last Tycoon had Robert De Niro, Anjelica Huston and Jack Nicholson. John Huston who found a second career as an actor in this era (for Chinatown) actually directed some of his most acclaimed films in The '70s (including Wise Blood and The Man Who Would be King).

- Likewise, Robert Mitchum still appeared in a few notable films in the era (The Yakuza, The Friends of Eddie Coyle) (and he would continue to act till The '90s), John Wayne and James Stewart made their final film appearances, William Holden appeared in Network and in The Wild Bunch (alongside other classic western character actors). Sterling Hayden likewise capped off his career by appearing in The Godfather, The Long Goodbye and the American-Italian production 1900.

- The overlapping trajectories of director-writer-producer Blake Edwards and actress wife Julie Andrews in this decade provide an extreme example of this trope for New Hollywood. In 1970 their World War I-set musical dramedy Darling Lili was just another nail in the coffin for the "roadshow musical" boom that had followed her 1960s megahits Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music and both of them were seen as relics. Flash-forward to 1979, and with Edwards having reversed his fortunes by reviving The Pink Panther series (a harbinger of franchise filmmaking to come) he brought out 10 (1979), a very-of-its-moment midlife crisis comedy that furthered Andrews from her squeaky-clean reputation, launched the last great pin-up starlet of The '70s in Bo Derek, and also proved to be Dudley Moore's Star-Making Role in Hollywood and thus another example of the many unconventional movie stars of this era. For bonus points Edwards and Andrews went on to do S.O.B., which fictionalized and satirized their Darling Lili travails.

- The posthumously released The Other Side of the Wind by Orson Welles, finally released in 2018, is more or less a time capsule of the '70s cinephilic industry. Orson Welles via his alter-ego Jack Hannaford (played by John Huston, another old relic keeping up with the times) voices his angst about the fact that many of the young film-makers calling him and others "old master" makes it hard for them to find and make new work, while also struggling to make films on account of the generation gap. On account of being made and released so late, the distance between TOSOW and the contemporary era is greater than the period between the Golden Age and the '70s, and many of the cameos by contemporary film-makers like Dennis Hopper and Claude Chabrol, become poignant on account of their passing in the interim.

- By the time of The New '10s, most of the generation of the New Hollywood have faded away, with some of them dying (Peckinpah, Hal Ashby, Michael Cimino, Robert Altman), seeing their careers going on skids and the margins (Coppola, DePalma, Bogdanovich), suffering controversy (Woody Allen, Roman Polański) or simply retiring (George Lucas). The only major directors with active ongoing careers and who have maintained Auteur License and prestige in the interim, as noted by Bogdanovich himself, are Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.

- Road Movie: Another genre really invented in this era, owing mostly to the new technology and lowered costs of productions that made it easier to shoot on location as well as in cars and moving vehicles. Easy Rider was the Trope Maker and Trope Codifier and the other films include The Rain People (by Coppola), Two-Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman), Slither (Philip Rieff). This genre also overlapped with the Outlaw Couple genre (Bonnie and Clyde, The Sugarland Express), and horror (Duel) and even science-fiction (the Richard Dreyfuss section of Close Encounters of the Third Kind).

- Romanticism Versus Enlightenment: On the whole this entire era was a long delayed Enlightened backlash to the rosiness of the Golden Age. Within the movement, Scorsese, Altman, and Woody Allen are closer to the Enlightenment side, while Coppola, Spielberg and Lucas are on the Romantic end of the equation.

- Stay in the Kitchen: Subverted but also Played Straight:

- Many of the Hollywood movies of this era revolved around the fact that women's liberation radically altered previous ideas about love, marriage, relationships and societies, and many films dealt with divorced couples, exes and blended families.

- However, as noted by Julie Christie in A Decade Under the Influence, this didn't necessarily lead to more and better roles for women. She noted that in most cases, films made in this era still focused more on male angst and that the decade largely ushered in a revolution for different kinds of male leads (in sexuality/race/religion/ethnicity/occupation) while women had at best only marginal improvement in the kind of roles they got, while women in these films still remained Satellite Character to men. By contrast, the Golden Age had recognised the importance of women as an audience and released big budget films specifically for women with strong female leads (Now, Voyager, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, The Harvey Girls, Meet Me in St. Louis and Imitation of Life (1959) most notably).

- This trope was however brutally deconstructed in The Stepford Wives - a film that could only exist in the 70s. Made right in the middle of the Divorce Revolution, the film satirised the lengths some men would go to in order to uphold more conservative values in this case replacing liberated feminist wives with submissive robots.

- Vigilante Man: This archetype appeared in this era. Dirty Harry was the first, Straw Dogs (1971) offered an Unbuilt Trope, Death Wish came later, and Taxi Driver served as a Deconstruction, though paradoxically, it was the last film that actually went on to inspire an assassination attempt. Abel Ferrara's 1981 Ms. 45note provided a Distaff Counterpart.

- Villain Protagonist: When they weren't outright anti-heroic, they were this. The flagship movie of this era is of course, The Godfather, whose protagonist is a crime boss. Other movies in that vein include Mean Streets and Taxi Driver.

Key Filmmakers of this Era (with their own pages):

- Woody Allen (Annie Hall, Manhattan)

- Robert Altman (M*A*S*H, The Long Goodbye)

- Hal Ashby (Harold and Maude, Being There)

- Ralph Bakshi (Fritz the Cat, The Lord of the Rings)

- Mario Bava (A Bay of Blood)

- Warren Beatty

- Peter Bogdanovich

- John Boorman

- Mel Brooks (The Producers, Blazing Saddles)

- John Carpenter

- John Cassavetes

- Michael Cimino (The Deer Hunter, Heaven's Gate)

- Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather, Apocalypse Now)

- Roger Corman

- Brian De Palma

- Clint Eastwood

- Miloš Forman

- William Friedkin

- Dennis Hopper

- Tobe Hooper

- Stanley Kubrick

- George Lucas

- Sidney Lumet

- Terrence Malick

- Elaine May

- Mike Nichols

- Alan J. Pakula

- Sam Peckinpah

- Roman Polańskinote

- Bob Rafelson

- George Romero

- Ken Russell

- John Schlesinger

- Paul Schrader

- Martin Scorsese

- Steven Spielberg

- John Waters