This section deals with events in Europe and Africa. In summary:

- It starts off in August 1939 with Germany and the Soviet Union occupying Poland in just a month, the Soviet Union later waging and eventually ending an inconclusive war against Finland that winter. In April 1940 Germany seizes Denmark and Norway to preempt the Allies' attempts to strong-arm Sweden into embargoing Germany, and on 10 May executes a crazed but amazingly effective two-month campaign through the Netherlands, Belgium, and into France. Italy joins the war on Germany's side and by the 22nd of June, Germany occupies all of Norway, The Low Countries and northern France. Having suffered a coup by military leaders Marshal Pétain and Admiral Darlan, the French Government votes itself and the Third Republic out of existence by giving Pétain absolute power. The new "French State" (dubbed "Vichy" France by its enemies) becomes a subservient rump state to Germany. Despite British attempts to capture and/or destroy it so it cannot be used to aid a German invasion of Britain, Germany refrains from seizing the remainder of the French fleet in return for Pétain's cooperation. Pétain and General Franco both refuse Hitler's offers to join the Axis of Steel note . German irrecoverable losses (captured, crippled, dead) c.20k Polish Campaign + c.30k French Campaign, Poland c.70k + France c.100k (post-surrender Poland c.500k, France c.2m captured), Commonwealth c.20k.

- Hitler is exasperated when Mussolini declares war on Greece for no good reason note . Germany prepares to bail Italy out of Greece because they fear that Britain will use Greek airfields to bomb the oilfields and refineries of Ploesti in Romania — Germany's source of virtually all petroleum products besides minor oil wells in Hungary, limited-capacity synthetic plants, and so-expensive-it's-basically-robbery purchases from the USSR. Yugoslavia suffers a British-backed coup and leaves the Axis, so Germany invades it to get to Greece note . British Commonwealth air forces note confront the Axis over Britain and North Africa. German irrecoverable c.10k, Commonwealth c.20k

- Germany launches Operation Barbarossa to destroy The Red Army in three weeks and occupy the European part of the USSR within two months on the 22/6/1941 with 2 million men, 3k tanks note , 3k planes note 624k draft horses, and 120k trucks along three 'fronts' and managed by three Army Groups under a new General Headquartersnote . The Red Army's two-million-strong forces along the central-northern German-Soviet border are caught totally by surprise and in just two weeks are at least nominally trapped in pockets based around Bialystock, Galicia, and Minsk, though measures to prevent them from just sneaking out the eastern side of the lattermost are miserablenote . Wehrmacht loses 1/6 of horses and 1/5 of supply-trucks in the first month due to malnutrition, exhaustion, and Red Army straggler attacks on rear-area troops. Kiev Military District forces, remnants of Western Military District, and reserve forces numbering 2 million stop Heer advance dead at Smolensk and Kiev by early August note . Massive internal disagreement flares up; Hitler wants to target resource-rich Ukraine, whereas the majority of the high-ranking officers note believe seizure of Moscow necessary to end war before winter and have tried to make this happen behind Hitler's back. note . Hitler is persuaded that defeating the Soviet Union will require defeating their remaining forces, which Halder and von Brauchitsch argue will be around Moscow… but, to their frustration, Hitler overrules them by insisting that Ukraine and Leningrad must come first. German irrecoverable c.100k, Soviet c.2 million (majority captured or missing as partisans).

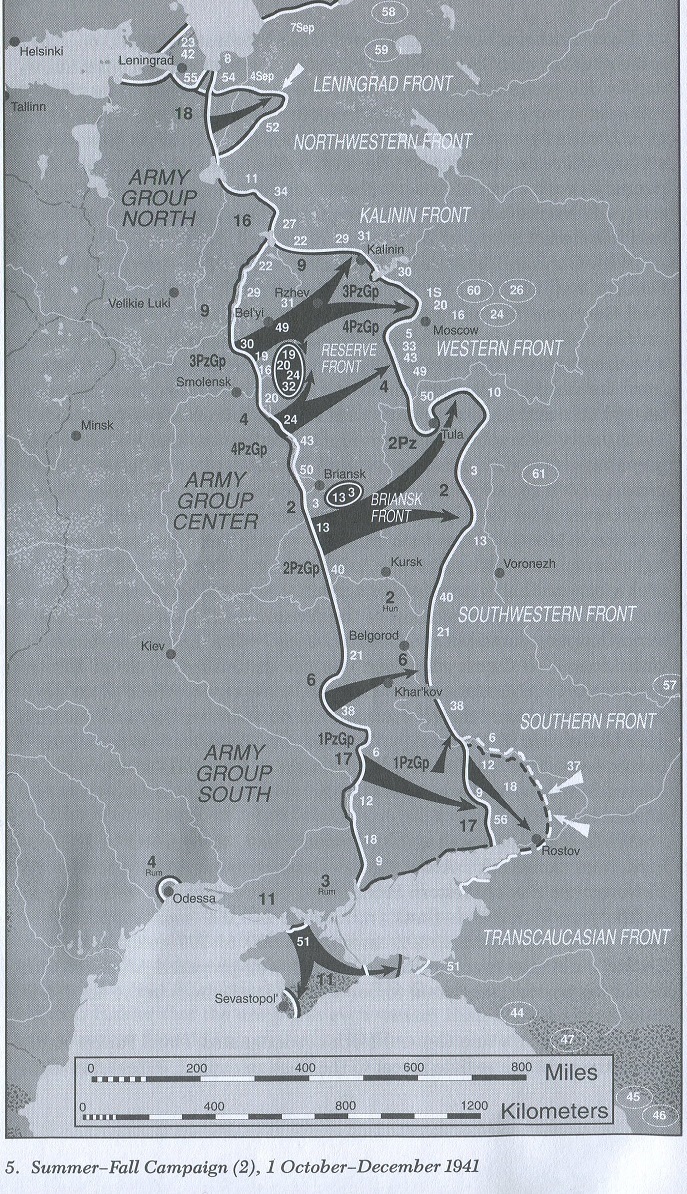

- Germany's August 1941 Kiev offensive detaches half of Army Group Center's mobile forces and throws Army Group Center's entire truck-pool behind them, giving them just enough fuel and ammo to slowly knaw their way south over a month-and-a-half of combat. Half of Army Group Center's remaining mobile forces are then sent north, to help Army Group North take Leningrad. The Soviet high command (Ставка, Stavka) under Zhukov urges Stalin to order withdrawal from the Kiev salient on the grounds that it is a death-trap that cannot be held, but Stalin refuses and has Zhukov reassigned to the Leningrad sector for his honesty. Soviet forces are driven back to Leningrad, but Army Group North has been so weakened by the fighting that a direct assault on the city is ruled out as suicidal—Siege of Leningrad begins. Army Group South's remaining mobile forces strike north in the last fortnight of September, and desperate Soviet break-out attempts fail. No sooner is the pocket crushed than, at the beginning of October, Army Group Center initiates Typhoon. One million troops opposite Army Group Center are trapped in three pockets around Vyazma, but advance slows to a crawl as Belrussian fuel stockpiles are totally expended. Rasputista, 'season of mud', then forces German forces to halt and pillage area to survive while advance continues with just 20,000 troops using all available tanks & halftracks—10k militiamen & NKVD are killed using AA guns to fight delaying actions in towns. Ground freezes in December, crippling German supply chain note . Advance dead on its feet—all available food and clothing already stolen from locals, fuel and ammunition supply at under 10% of offensive requirements. Soviet counterattacks meet with more and more success. Heer retreats become routs. Stalin declares a Winter Counteroffensive in January with two million troops against million-strong remnants of Army Group Center, half-million men of Army Group North. Aims are to break the Siege of Leningrad and encircle the entirety of Army Group Center, a bold attempt to win the war at one stroke note . At same time (7 December 1941), Japan executes her Southern Offensive Campaign against Britain, Netherlands, and the United States. That month, Hitler also declares war on the United States. German irrecoverable c.400k, Soviet c.2 million (majority captured or dead).

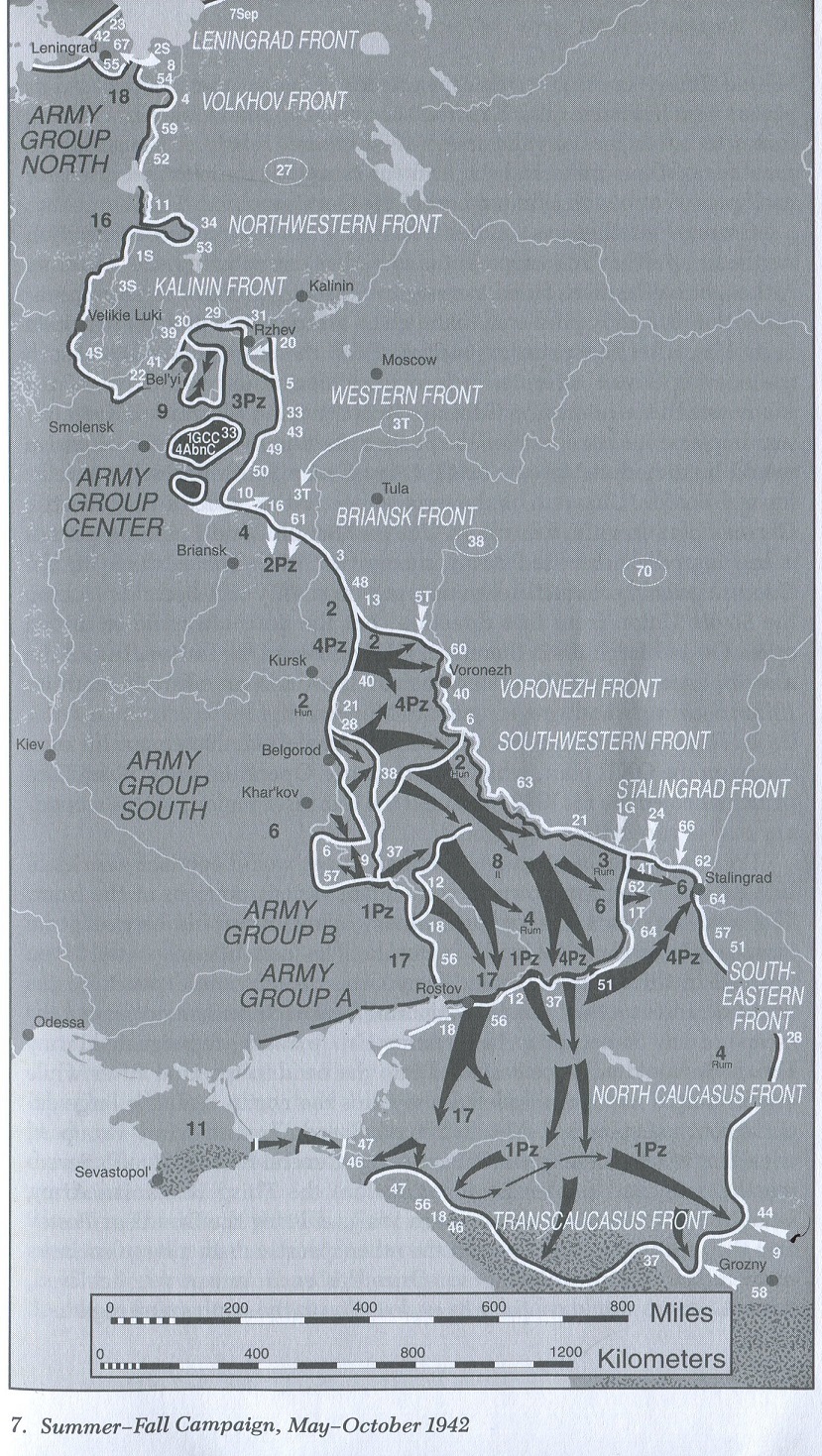

- By late June the Soviets' Summer Offensive Operation has bogged down trying to attack Army Group South. On 28 June 1942, Germany's Army Group South executes Case Blue to take east Ukraine and the oilfields of the Caucasus, quickly encircling and capturing the Red Army Summer Offensive forces and leaving the whole Ukrainian front critically weakened, Stalin moving his reserves to prevent them from driving on Moscow. Army Group South is split into Army Groups A and B and set to take The Caucasus and defend their flank near Stalingrad respectively—but at the last minute Hitler takes forces from the former so the latter can capture Stalingrad, causing both forces to fail. On 19 November the Soviets deploy half of the massive reserves they've been hiding in the south in Operations Uranus and Saturn—trapping 100,000-200,000 Italian and Romanian and a similar number of German troops in a "pocket" around Stalingrad, then pushing the Germans out of the Caucasus entirely. The Soviets have kept the other half of their reserves in plain sight for use in Operation Mars (25 November 1942) to break the back of Army Group Center—but they fail with heavy losses because the Germans were expecting it and had deployed their own reserves there to counter them. When the last starving survivors of the Stalingrad pocket surrender at gunpoint in February 1943, only 91,000 German troops are left. The offensive against Army Group North to break the Siege of Leningrad is unsuccessful, and on 19 February-15 March the Red Army's pursuit of the reconstituted Army Group South is crushed by a counteroffensive led by Panzer forces redeployed from Army Group Center and Army Group A (formerly deployed in the Caucasus) in the Donets counteroffensive. German irrecoverable c.300k, Hungarian+Romanian+Italian c.400k, Soviet c.3 million

- Although Erwin Rommel's German Expeditionary Force (of just one division!) in North Africa was originally just meant to prop the Italians up and avoid making them look bad, North Africa has effectively turned into a "fifth front" for Germany, with Rommel commanding half as many troops as Army Group B. Given that North Africa has zero strategic importance, deploying troops (let alone combat!) here is not something that Germany can actually afford note . Although the Italians manage to transport more-than-sufficient supplies to their depot in Benghazi in the face of harassment from British Malta, the road-supply chain from there to Cyrenaica and Egypt is a thousand kilometers longnote and Rommel's troops starve as their food rots in the docks at Benghazi note . After some back-and-forth action the Western Allies eventually push him back into Tunisia, with U.S. troops occupying French North Africa and pushing eastward. Although the Allies, and the completely inexperienced Americans in particular, make some serious blunders this only persuades Hitler to send even more men to the North African Front so he can avoid admitting that they shouldn't be there in the first place… all 100k of whom surrendernote when the Allies finally break through and encircle them. Noting the importance of tea in the African theater as a way to make the awful water taste better, the British government buys the entire world crop in 1942. German irrecoverable c.100k (majority captured), Italian c.400k (majority captured), Western Allies c.20k

- The Donets counter-offensive has created a prominent bulge in the Soviet-Axis lines around the city of Kursk. On 5 July 1943, the Germans launch Operation Citadel to cut it off and thereby shorten the front, but the Soviets are ready for them and to their shock and dismay they fail utterly note . On the 10th of July, the Allies use staging posts in North Africa to execute operation Husky, liberating Sicily, whereupon Hitler acknowledges the failure of Citadel and orders some of its mobile forces to Italy. The Soviets follow up with an offensive in Belarus, which the OKH has to divert their already-exhausted Panzer formations to to prevent them from breaking through in earnest. No sooner is the front there stablized than the Soviet forces in the Kursk bulge go on the offensive and make a huge breakthrough around Kharkov-Kiev, forcing the Germans to divert their mobile forces south again. No sooner is that front stabilized then the Soviets execute the Don offensive in southern Ukraine… then another northern Ukrainian offensive… then the Lower Dnepr offensive… and then, after that year's Rasputitsa, the west-Ukrainian Korsun offensive that winter—generally accepted as the death knell of Germany's experienced Panzer forces. With Army Group North's strength having been steadily eroded by four failed Soviet offensives, constant raids, and neglect by the OKH the Red Army finally manages to force open a corridor to the city in the winter '43 Leningrad offensive, lifting the siege. The Allies execute operation Baytown and land in Southern Italy, resulting in a coup in which Mussolini is toppled and Italy joins the Allies. Germany quickly occupies northern Italy and establishes a series of fortified defensive lines across the hilly peninsula. The Allies' Italian front continues to gradually push northward in the years to follow, but the going is slow and the forces on both sides remain small with fewer than a million combat troops on both sides. The Allied strategic-bombing campaign helps the Red Air Force achieve air-supremacynote and begins to cause serious disruption to German industrynote as the air-war turns against Germany despite the full mobilization of Germany's resources for 'Total War'. German irrecoverable c.500k OKH/Ostfront c.50k OKW/Other, Soviet c.1 million, Western Allies c.100k

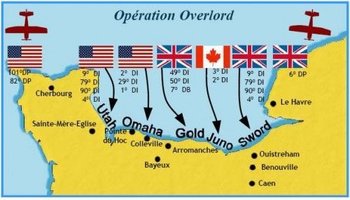

- On 6 June 1944, the Allies implement Operation Overlord and successfully establish a beachhead at Normandy, northern France. As Germany scrambles to keep them contained, on 22 June General Rokossovskiy's forces catch the Germans off-guard by launching a double-envelopment offensive into Belarus and not Poland note - operation Bagration. Sealing up half of Army Group Center's forces in a pocket east of Minsk, they then barge aside the rest and an eclectic mix of German reinforcements on their way south and west to northern Poland and the Baltic States. The Germans divert forces from eastern Poland to slow them down, whereupon the Soviets execute the second phase of Bagration—from Ukraine into Poland. The sites of former extermination camps destroyed by the retreating Germans, including Treblinka, fall into Soviet hands. Soviet-backed Communist Republic of Poland is established in city of Lwow, and in response British-backed Polish Government-in-Exile orders Polish 'Home Army' to rise up and liberate Poland before Soviet and Communist Polish forces arrive in the hopes of establishing anti-Communist Polish regime. Home Army forcibly incorporated into Army of Communist Poland, with Soviet help, or crushed by German forces. Warsaw Uprising falls to mix of Foreign-SS, Green Police, Luftwaffe, and Army units after two months of urban warfare. With German counterattacks in Prussia and Poland stabilising the front at Germany's pre-war borders and along the Vistula, the Soviets launch the Iassy–Kishinev offensive into Romania that September note . When Romania switches sides, Bulgaria and Finland follow suit and the Soviets are poised to invade Hungary by the time the Rasputitsa arrives. Half of Germany's entire 22-June stock of combat troops has been killed or captured note and their replacements are woefully inexperienced. Army Group North is cut off in the Baltic states by a daring offensive into East Prussia. Allied troops have captured 50,000 German troops in the Falaize Pocket and broken out of Normandy; facing forces more than three times the size of her ownnote , Germany's defeat is imminent. The Soviets and Allies take Romania and France and get bogged down in Hungary and the Low Countriesnote respectively. As the Red Army's Hungarian Offensive against German Army Group South grinds on into its second month, a German force of about the same size (c.300,000 men) launches a counteroffensive—codenamed Operation Wacht am Rheinnote —against the Western Allies (primarily Americans) in Belgium on 16 December in what will become known as the Battle of the Bulge. Despite limited initial success, it's soon bogged down and is cancelled on the 25th of December, the forces involved being ordered to withdraw as the Red Army completes its encirclement of Budapest by the 26th of Decembernote . Hitler orders that the siege be relieved by Panzer forces withdrawn from the French and Polish fronts, but Operation Konrad grinds to a halt south of the city before the Red Army counterattack goes on to encircle them. Only food and fuel shortages—unlike Hitler, 'Stavka' considers the Hungarian front to be of secondary importance—prevent the Red Army spearheads from entering Austria immediately. German irrecoverable c.500k OKH/Ostfront c.100k OKW/other, Hungarian+Romanian c.200k, Soviet c.1 million, Western Allies c.200k

- Upon Churchill's request, Stalin makes a big show of bringing the Vistula-Oder offensive forward by eight days to 12 January. Its goal of taking Berlin (which was too ambitious anyway) is downgraded to merely taking bridgeheads across the Oder to facilitate a final push on the German capital later. The inexperienced and ill-equipped German forces being outnumbered by more than 4:1 (2.2 million to 450,000) it succeeds with minimal losses and great speed, one consequence of which being that Auschwitz extermination camp is liberated largely intact despite German desires that it (like Trebilinka and the others). However, German forces are far from exhausted and Stalin wants great care to be taken to liberate the bulk of German industry (concentrated in Silesia, in the west of today's Poland, to protect it from Allied bombing) intact. Accordingly Rokossvsky's front is tasked with grinding its way to the coast of East Prussia (even in the face of fanatical German resistance, such as that at Königsburg) and Koniev's is ordered to use sophisticated manoeuvres to encourage the Germans to retreat from Silesia with due haste and a minimum of fighting. Stalin and Churchill hash out the definitive Soviet-Allied zones in Europe as Hitler juggles what's left of Germany's Panzer forces through two last counteroffensives, February's Operation Solstice and March's Operation Spring Awakening, to relieve pressure on Berlin and retake the Hungarian oil fields respectively. Both fail with heavy losses, the latter greatly expediting the Soviet advance into Austria. The "prize", and price, of taking Berlin is left to Stalin note The race (between Marshals G.K. Zhukov and I.Y. Koniev) to take Berlin starts on the 16th of April, with Soviet forces quickly meeting up with American troops at Torgau on the Elbe. Hitler commits suicide in his bunker and on 8 May 1945, with the red Soviet flag flying over the Reichstag, the new Reichspräsident, Großadmiral Karl Dönitz, surrenders unconditionally to the Allied Expeditionary Force and Red Army Command (represented by Zhukov). Stalin prepares to honour his deal with the Allies by transferring his best mobile units from Europe in preparation for the Red Army's Far Eastern Offensive Operation against Japanese forces in China that August, and some U.S. troops are also redeployed to take part in October's Operation Downfall. German irrecoverable 2 million (majority captured), Soviet c.500k, Western Allies c.50k

While we are perfectly aware that 'Blitzkrieg' was not a German military term, but an Anglo-American word used to describe a mixture of German combined-arms Battlefield Tactics and Operational-level encirclement manoeuvres, it is a useful shorthand and is too entrenched to be dismissed. However, kindly distinguish between the decentralized-and-flexible Tactical command principle of Auftragstaktik ('mission-based tactics') note and the Operational emphasis on Bewegungskrieg (mobile warfare) note .

World War II combat operations begin with the Nazi invasion of Poland, preceded by a series of False Flag Operationsnote . Britain and France declare war on Germany, beginning the Western Front, but they don't actually do anything to help beyond imposing a blockade and the latter initiating a limited offensive into the Saar region.note Initially, their Western Allies and Germany are shocked by the Polish armed forces' capabilities. While they are losing to the Germans, they are losing slowly. Weapons like the Model 35 Anti-tank rifle are able to do horrific damage to the early panzer models when combined with Polish cavalry's mobility. But a one-on-one fight will end with defeat without significant Western intervention. Poland's odds get even grimmer as their old enemy, the Soviet Union, invades from the east to make good on their part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Poland's regular forces are crushed within five weeks. While they only last a week and a half less than France will, the Poles damage or destroy no fewer than 11,000 enemy vehicles, achieve a 2:1 armored kill ratio in tank-on-tank battles, and inflict 40,000 casualties on the Nazis. While the Fuhrer is elated with the victory, the Wehrmacht is concerned at the fact these Polish Untermenschen managed to inflict so much damage.

That said, neither the Germans nor the Soviets manage to round up all of the now-former country's military personnel, and these living loose ends will cause trouble later. Some, like the Polish air force—many former pilots of which join the Royal Air Force—flee the country and fight alongside the Allies, and others form resistance groups and await the time to strike. Polish intelligence forces are also able to share all their decryption information on the German enigme machine with their Western Allies.note The Soviet Union follows up its acquisition with the quiet annexation of the Baltic States of Latvia, Estonia and even Lithuania; althought the latter was supposed to be a German-dominated state in the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, the Soviets want it as it had been part of the Russian Empire and the Lingua Franca there is actually Russian (the Soviet Union's official language). The Germans hastily revise the treaty so Lithuania's in the 'Soviet Sphere' and the Germans aren't legally obligated to go to war with the USSR over it.

On the naval front, the Battle of the Atlantic begins slowly. The German Navy has learned many lessons from its experience of commerce-raiding in the First World War and the new Commander of U-boats, Admiral Karl Dönitz, has been planning for a new submarine war for nearly twenty years. He and his staff expect the British to quickly adopt the convoy system, which had led to a sharp decline in sinkings by U-boats when the Royal Navy finally conceded it was necessary in mid-1917. In addition, the British have developed sonar (a form of remote-detection device that uses sound-waves) and are confident they can easily locate submerged boats. However, German U-boats will spend most of their non-attack time surfaced for practical reasons (as they have limited range and speed while submerged) and to reduce the effectiveness of sonar. Dönitz has also developed new doctrine to counter convoys: submarines will scout out, converge upon, and follow convoys by day. Then, they will attack under the cover of darkness when the convoy escorts' sight-based anti-submarine weapons will be least effective. Unfortunately, he has less than a fifth of the submarines needed for strategically significant operations, the fleet expansion and rearmament program is nowhere near complete, as Dönitz and surface fleet commander Grand Admiral Erich Raeder were under the impression that war wouldn't start until 1943 at the earliest.note . Nevertheless, he sends his "Grey Wolves" into the North Sea to begin sinking ships. One of them, U-47, is sent into Scapa Flow, the main naval base in the British Isles, and sinks the battleship HMS Royal Oak before escaping unharmed. The British are stunned.

The Red Army's subsequent poor performance comes as a surprise to everyone bar themselves, as they had done quite well in a border clash with Imperial Japanese Army on a disputed patch of Communist Mongolian/Mongolian Kingdom soil just a year before at Khalkhin Gol. This textbook example of a successful small-scale encirclement operation saw the Soviet operational commander, Colonel Georgiy Zhukov, later appointed to the post of Chief of the General Staff (Stavka) after the Winter War. The operation also encouraged Japan to agree to an non-aggression pact with the USSR, expiring in 1946. Returning to the war at hand, the Red Army wasted no time in touting the failed operations of the Winter War as damning indictments of its own degraded capabilities:

- The supply services were completely unprepared to sustain the campaign due to the utter lack of prior planning, forcing extensive improvisation and therefore waste and inefficiency. Moreover the supply services functioned inefficiently, with throughput being insufficient for the troops' needs.

- Maps were not drawn up, printed, and issued in the required scales and numbers.

- Weather and geography were rarely anticipated or accounted for, resulting in delays and chaos when they inevitably affected the actual conduct of operations.

- Aerial, artillery, engineering, and infantry observation was not adequately conducted. Even when sufficient data was collected, it was not processed competently or in a timely fashion. The locations of enemy fixed defenses and troop concentrations were largely unknown.

- Combat Reconnaissance and Deep Reconnaissance were not conducted, leading to a total inability to identify defensive positions, troop concentrations, and artillery concentrations in the enemy rear areas outside full-scale combat.

- Infantry and artillery forces failed to communicate frankly and plan joint operations. Consequently many infantry attacks were conducted with little or no artillery support. Poor observation, reconnaissance, and data-processing times meant poor accuracy in bombardments requested during attacks and a near-total inability to target and suppress enemy artillery in a timely fashion.

- Engineers were often used in generic combat roles with no regard to their proper use in assaulting enemy fortifications, dismantling enemy minefields and obstacles, and creating and repairing infrastructure in the rear areas.

When the Leningrad Military District's assaults on the Karelian Isthmus (the most direct path from Leningrad to Helsinki, with an actual railway line) failed, the ineffectual General Meretskov was replaced by the utterly incompetent Kliment Voroshilov, Stalin's old Civil War buddy. Voroshilov decided that, rather than identifying or fixing any of the problems with his force's organisation and deployment, he'd simply have them flank the isthmus through 200km of dense and uncharted swamps and forests. This worked out about as well as one might expect, with his force's many isolated and overextended columns being cut to ribbons by Finnish hit-and-run raids. At this point even Stalin recognises that Voroshilov isn't up to the task and allows him to be replaced by Semyon Timoshenko—not an inspired commander, but a decent one who commands the respect of both his peers and Stalin. Timoshenko works with the General Staff to identify and begin to correct the problems listed above, ordering increased observation and reconnaissance while improving artillery/infantry coordination. This doesn't solve the processing issue, but it allows his forces to finally make some inexorable headway—even if the going is slow.

Soviet forces are poised to clear the Karelian isthmus and break into the open country when the USSR strikes a peace deal with the Finnish government, wanting to avoid open hostilities with the Allies—the invasion had provoked such widespread international condemnation that Britain and France were poised to dispatch an expeditionary force to assist the Finns, which would have meant open war (or at least sanctions and a blockade) and therefore an end to the USSR's foreign trade. As a grain, steel, and oil exporter, one might assume that the Soviet Union would not have been particularly bothered by this. However, the current five-year plan is focused on trying to build up the number of transport trucks (which are all, not at all coincidentally, military grade) in the "civilian" economy and Red Army. For that they'd need tires. And while the Soviets can produce synthetic rubber from coal, they'd much rather buy the natural alternative from Anglo–Dutch southeast Asia and South America.

The Winter War worked out badly in that was a costly failure which diplomatically isolated the Soviet Union, but it worked to their advantage given that it utterly discredited figures like Kliment Voroshilov who had been denying (in his case quite possibly sincerely) that the Red Army's effectiveness had been degraded by the fatal combination of purges and rapid two-fold expansion. It put the faults with the post-purge Red Army on display for all the world to see and forced Stalin to recognise that the Red Army had to be reformed, with figures such as GRU (military intelligence directorate) chief Colonel Ivan Proskurov metaphorically tearing Stalin a new one in secret military councils called to determine just what the hell went so very bloody wrong. The Red Army's abysmal performance had wider implications because it was pretty much the only case study that the Fremde Heeres Ost (Foreign Armies Ost) department of the German Army's General Staff had to go on when making assessments of the Red Army's effectiveness. To the Germany Army's detriment, in late 1940 the FHO would conclude that the entire Red Army would be every bit as incompetent in mid-1941 as it had proven in the winter of 1939-40—so incompetent, in short, that it would be totally incapable of defending the USSR from a German invasion.

Finland agreed to a harsh peace because it had been economically and militarily incapable of continuing the war, and everyone knew it. That they lasted so long is a point of real pride for the Finns and a cause of serious concern for Stalin, who came to understand that the reforms he instituted to politicize the Red Army were a bad idea and have severely impacted its fighting ability. One concrete result is that Commissars are reduced to their pre-1937 status of mere advisers and liaisons with the Communist Party, rather than being co-leaders of their units. He also accelerates the armaments program, which should see the Red Army become the most modern and lavishly-equipped fighting force in the world by 1943 or so.

The Allies had been extraordinarily keen to get Finland on their side as part of their wider strategy of blockading Germany. They even put together an expeditionary force to send to Finland, should the latter formally ask them for it. This is because having ground troops in the area, who could use Finland as a base, would allow them to project their (military) power into the Baltic and hopefully get Sweden to stop exporting steel to Germany (by "offering" to buy it themselves). As it turns out, the Germans preempt Finland and the Allies by seizing Denmark and attacking Norway in a surprise offensive, thereby making the Allies' diplomatic overtures meaningless as Germany now controls access to the Baltic. The task force is diverted to Norway, but too late; the Germans' hold over the country is already too strong, and the Allies have to withdraw. Over the coming months, Germany soon draws neutral-but-Axis-sympathetic Sweden and a now-embittered, staunchly anti-Russian and anti-Soviet Finland into their orbit…

On a brighter note, the campaign finally gives a name to what may be history's most famous improvised weapon. When the Soviets started dropping cluster and incendiary bombs on Finnish towns, Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov claimed they were actually dropping food—"Bread Baskets"—for the starving Finnish proletariat. The Finns subsequently dub their improvised petrol bombs—of the same type used by desperate infantrymen trying to take out tanks in China and Spain—"Molotov Cocktails". "Cocktails", because they're a drink to go down with the "bread". Appropriately enough, a majority of them were filled with high-proof grain and potato spirit rather than petrol and were manufactured by Finland's government-controlled liquor monopoly.

Scandinavia Proper had declared neutrality when war broke out. When Finland was invaded, Norway quickly chose sides, and through public fundraising, backpacks and warm clothing was shipped off to Finland in a hurry during the end of 1939. What Norway and Denmark didn't know was that Germany had plans for them…

Intelligence heated up, and so did political debates during the winter of 1940. In February, the German tanker Altmark passed through Norwegian waters, carrying prisoners of war. The prisoners were actually British, taken during the Graf Spee incident off the Brazilian coast, and the prisoners were ferried the long route to avoid attention. Norwegian navy and coastguard contacted the Altmark repeatedly, and the ship was eventually boarded by Norwegian navy personnel, inquiring the Germans on what the heck they were up to. As it were, the Norwegian navy took the Germans on face value and let the ship continue its southward course. The RAF spotted the ship later on and alerted the Royal Navy, who gave chase, acknowledging that the POWs were British. The Altmark sought refuge in a Norwegian fjord (Jøssingfjord) on the south-west of Norway, and after direct orders from navy minister Winston Churchill himself, the British asked for permission to board the ship. The Altmark ran aground, and the British went aboard, approaching the Germans in direct combat with bayonets. This skirmish was the first actual confrontation between British and German troops, and the Germans lost eleven soldiers. The incident sped up the German plans for invasion of Norway, because Hitler by this time understood that the British might have some strategic interests there as well.

The neutrality line had to be preserved. The Altmark incident was debated in Norway because both the British and the Germans had violated Norwegian neutrality (underscoring the point that the British authorities had declined to alert the Norwegian coastal guard, and the Norwegians likewise had not contacted the British on the identity of the POWs). The local fascists, however. had already begun their moves. Thus, Vidkun Quisling had already made a trip to Germany, assuring Hitler that Norway would cooperate if necessary. He was, of course, at odds with his own government over this. Great Britain was also wary that Norway might fall under German influence, because of the iron shippings from Narvik. This argument was used by Norwegian collaborators later on. During the crucial end of March and beginning of April, Britain and France mined parts of the Norwegian coastline, stirring a debate in the Norwegian parliament on what exactly the British were up to.

The question of mobilizing in case the British were about to invade was in fact turned down by the king himself, because of his tight connection to the British royalty, and because king Haakon understood that this would put Norway on the German side against the UK, which he wisely avoided.

The British, especially Navy minister Churchill, actually had plans for an invasion of Norway, securing the Iron line from Kiruna to Narvik, and thus hindering the Germans in getting their hands on it. As it turned out, Nazi Germany beat them to the punch, having the plans ready for assault by March 26. The first flotilla embarked April 6, heading for Narvik. At this point. the British had mined the Norwegian route from Narvik to make it difficult for the Germans to use the iron lane. Churchill had come up with this idea in the autumn of 1939 already, but it was executed in April 1940, while the Germans already were on their way. The iron mines were Swedish, and the Narvik port had been built by the British. Sweden, being neutral at the time, never came in harm´s way during the war, and became a hotspot for information, diplomacy and massive scolding from Norway at the beginning of the Norwegian campaign.

The crossing of interests between UK and Germany were mirrored in the Norwegian debate. The fascists supported Germany, and used the Altmark incident against the British. The fact that Germany actually invaded first, tipped the greater part of Norwegians over to the British side, and pitted them thoroughly against the Germans. When the Germans eventually did invade, they explained their actions with the argument of "protecting Norway and Denmark against western aggression", blatantly ignoring the fact that the Reich had provoked war in the first place. This flyer, written in Norwegian with a vague German fling to it, was spread over most of Norway, and promptly ignored.

German embassies in Norway were well aware of the invasion plans, and used a lot of propaganda to keep Norwegian public and officials from acting rashly. Thus, a movie made from the bombing of Warsaw was shown at the very beginning of April, to underline the point of what the Wehrmacht actually could manage. Meanwhile, a Norwegian journalist in Lübeck telegraphed home on an alarming mass of ships scheduled for the North Sea. The telegram was received, but the headlines never got printed. The military leadership, and even the government, was alerted about this, but forces inside the Joint Chiefs of Staff advised caution. The invasion began on the morning of April 9. Denmark was attacked through Jutland. While some Danish units near the border offered some scattered resistance, the Danish government, under Prime Minister Thorvald Stauning and King Christian X convened at a crisis meeting in the early morning hours. Remembering the terror bombing Warsaw had been subjected to the year before, the Danish leaders feared that something similar could happen to Copenhagen, and as such came to the conclusion that offering any kind of serious resistance to the Germans was an untenable situation that would only lead to the needless loss of Danish lives. A general order of surrender was quickly handed down to the Danish armed forces, though some active fighting would still go on for a couple of hours, as the German attack had disrupted the lines of communication. All in all the German invasion of Denmark lasted about six hours. In a show of goodwill for the swift surrender, the Nazi government allowed the Danish state to keep their King and elected civil government and some modicum of autonomy, but only on the condition of the Danish government's continued and full collaboration with any German orders. In Norway, however, things would take a quite different course...

Using the now occupied Denmark as as a springboard, the Nazi war machine was able to attack Norway at several ports at once. Many coastal forts responded with what they had, and some cities, like Kristiansand, Stavanger and Bergen suffered heavy bombardment. Kristiansand probably had the worst of it. In the Oslo fjord, the German attack fleet suffered equally heavy losses, with the heavy cruiser Blücher going down with all hands.

This stalled the German invasion of the capital, and enabled the government and King to escape. They travelled through the country for two months, practically with the Wehrmacht at their heels in hot pursuit. By April 10th, the Quisling government had taken the helm, and offered King Haakon VII and his government "safe conduct" if they surrendered. The King made a stand, giving the laconic reply of "No" to the German ultimatum of surrender, something which the civil government quickly back him on. As a result the Germans had to fight their way into the country for two months. Local army units took to arms in many places, and made the best of it. The badassery of the local units kept the Germans at bay for weeks, until the Luftwaffe arrived. Some mountainous areas were so narrow, the Norwegians just fortified the mountainsides, knowing that German vehicles only had one small country road to use. The Germans understood rather quickly that the Norwegians just picked them off one by one. Then again—the Luftwaffe saved the German advance. Hitler was allegedly furious over the Norwegian lack of cooperation in the matter, and declared war by April 11, seeing to it that Norway became, and remained, a fighting Ally during the remainder of the war, although the Norwegian mainland was occupied.

In the north, Trondheim was taken without a gunshot (although the local fortress at Munkholmen opened fire), and the city of Narvik surrendered, most likely because the local army chief was a member of the Quisling party. This party counted some officers who surrendered sooner than others. Narvik suffered bombardment from the British, and the battle for Narvik was reknown because both French and British troops took part. In this battle, the Wehrmacht was pushed as far inland as the Swedish border and was on the verge of surrendering, when the British and French got news of the invasion of France. Cue a Heel–Face Turn, and a sudden Norwegian surrender.

Speaking of the British, the Royal Navy had actually intended to help Norway during April and May. Bad weather in the North Sea and a string of horribly bad decisions from the British high command gave the Germans every chance to win the campaign. This string of events led to the famous Norway debates in May, forcing Prime Minister Chamberlain to resign, leaving his place to Winston Churchill. The fact that he, as a minister of the navy, was in fact responsible for the naval blunders in the North Sea, was promptly forgotten.

Norway surrendered by June 10. But by then, the Norwegian government was in exile, and the Norwegian commercial fleet had been ordered to seek refuge in neutral ports. Thus, Norway was reckoned among the Allied forces, not as an occupied land per se. During the war, the Norwegian fleet secured a lifeline to the British Isles, making it possible for the British to endure German siege. The fleet suffered heavy losses because of this.

Between the fall of Poland and the German invasion of Scandinavia was an eight-month pause variously nicknamed the "Phony War", the "Sitzkrieg" (Sitting War), the "Drôle de Guerre" (Funny War), or the "Bore War" (a pun on the Boer War), in which the British and French mobilized all their industries and quietly churned out all the armaments they could, mobilising and organising all their reserves for a defence of the Low Countries while they sit behind their Naval Blockade and the Maginot Line. Germany does much the same in this period, but unbeknownst to the Allies the blockade strategy is near-totally ineffective—the Allies were right to assume that Germany had been largely unprepared for a war with them, and that the Nazis' strategic-resource stockpiles were very small. However, the Soviet Union is now trading with Germany as per the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and so numerous types of Unobtanium like molybdenum, tungsten, aluminium, rubber, and petroleum products are freely available to them... albeit at cut-throat prices. A brief spurt of excitement comes when Scandinavia gets involved—the Allies were considering getting involved there to stop Sweden supplying Germany with high-quality steel (a trade which was drastically less important than it appeared in the short term, as Germany was also able to get steel from the Soviets), but the Germans see this coming and attack Denmark and Norway to preempt them. This audacious attack in the face of Britain's superior seapower catches the Allies completely flat-footed, and the resulting confusion prevents the Royal Navy from intervening until it's too late, though the brand-new heavy cruiser Blücher is sunk and the pocket battleship Lutzow heavily damaged by the Norwegian shore batteries defending Oslo. While an Allied force (originally destined for Finland) manages to take the important Norwegian port of Narvik (through which Swedish iron ore is sent to Germany), they are in no position to hold it and are ordered to withdraw to France for a more important battle. Taking some of the sting from Britain's first major retreat, the initial Royal Navy assault on Narvik managed to sink a third of Germany's modern destroyers—a coup which, along with their other naval losses, will have serious repercussions later.

When the Germans do declare war on Belgium on May 10, 1940, the Allies are seemingly ready for them. The Allies have a numerical advantage in troops, artillery and tanks, and though the Royal Air Force and Armée de l'Air have fewer bombers than the Luftwaffe, they have more fighters. Almost all their troops have modern weapons with sufficient ammunition and the training to use them properly—France has had conscription for years, meaning that virtually all of the troops in their army have completed at least a year or two of military training. The Wehrmacht, on the other hand, is largely inexperienced and ill-equipped (though the veterans of the "Condor Legion" have disseminated their experiences from the Spanish Civil War, and the motorised small mobile force has also been bloodied in the invasion of Poland and the battles in Scandinavia even if the infantry are still overwhelmingly 'green'). The Allies' forces also have far more horses, trucks, and mobile/'motorized' troops (infantry units which use trucks to get around).

However, French military 'doctrine' has greater shortcomings than German doctrine does. 'Doctrine' is a shorthand term for the philosophy, 'how-to' guides, and structure militaries use for waging war. French and German doctrine is shaped by their First World War experiences, and neither is perfect. An 'operation' consists of a series of battles fought in pursuit of a strategic goal, the length of which is dictated by what is physically possible in terms of the required production, stockpiles, and throughput of supplies (ammunition, fuel, food, spare parts, and so on). German doctrine has two critical shortcomings regarding planning in that it has no concept of a war which is not over in the space of a single 'campaign' or 'operation', and the physical possibility of enacting the operation (in terms of supply requirements) is never considered in the planning phase. The problem with the planning of operations in French doctrine is even more fundamental: it doesn't recognise the existence of Campaigns/Operations. There is no such thing as a 'completely incompetent' Campaign/Operational-level German planner, as he always has standardised guidelines to thought and action to underwrite his performance. On the other hand, there is no minimum standard of competence for a French Operational planner.

French doctrine's flaws regarding the actual conduct of operations are also greater than the German. French doctrine is based around 'positional warfare': the seizure and defense of landmarks and territory on the battlefield. It emphasises the inexorable and centrally-directed concentration of overwhelming artillery and armoured assets on the battlefield to take territory and repel attacks at minimal cost through the expenditure of large amounts of ammunition. This is a modernised and frankly superb version of the slow-paced, methodical, low-casualty warfare which France perfected in 1918. German doctrine on the other hand is based upon a complete rejection of 'positional warfare' in favour of pre-WWI German theories of Bewegungskrieg or 'manoeuvre warfare': the rapid movement and concentration of forces at the operational level. It emphasises the ad-hoc movement of highly independent mobile forces to encircle operational-level groupings of enemy forces to defeat them at minimal cost through cutting them off from resupply. This is a modernised and passably-workable version of the rapid, chaotic, low-casualty warfare which Germany practiced against Romania in 1917.

In other words, the betting man would favour the Germans if they manage to keep the war mobile and the French if they manage to bog it down. If the war bogs down into positional warfare then the German Army will be completely incapable of making any headway against the French Army, or stopping the French from making headway of their own: the French, with their centrally-directed Artillery and Armour, will be tactically unstoppable. But if the Germans can strike a decisive blow while the situation is still relatively fluid and manoeuvre is still possible, then the French will be largely incapable of reacting in time to halt the German Army's movements or making headway of their own: the Germans, with their independently-acting mobile Infantry and Armour, will have surrounded and destroyed a significant portion of the French Army. Interestingly, this debate (Manoeuvre versus Positional Warfare) had already played out and been resolved in the Soviet Union: the victor was neither school of thought, with Vladimir Triandafilov combining the two into a new school of warfare which he called 'Deep Battle'. As he saw it, a Modern Army needed to be capable of breaking the deadlock of positional warfare as a pre-requisite to executing sophisticated operational manoeuvres and encirclements to net large hauls of prisoners. But more on that later.

The French high command under Gamelin decides that this time, the Allies will hold the line in Belgium at a series of major rivers while making good on their industrial-commercial advantage by further building up their forces, before (when the Germans are virtually out of fuel because of the blockade) pushing the Germans back across the border. They haven't, however, ironed out the details. Politicking within the high command (careers and reputations were at stake when the Allies' plans were devised) meant that only one plan (holding the line in Belgium and building up their forces) was fleshed-out in detail. Even so, it's a good idea (despite the whole "blockade not actually working" thing). Germany is the only Great Power not to have a high commandnote , but Germany's top generals and Hitlernote know all too well their forces' own inadequacies, and that the Allies' advantages will only increase with time. They are also uncomfortably aware of just how untenable their alliance with the Soviets is in the long term.

With all this in mind, Hitler has chosen to launch an offensive against the Allies through Belgium. Germany's small and out-classed force of armored and motorized units will use their superior speed and communications to punch a tiny opening in the Allied front and force their way through to wreak havoc behind Allied lines—and the rest of the German army will follow, on foot, to encircle half the entire French Army in one fell swoop by attacking where they least expect it! The old guard of Hitler's generals—who saw combat in World War One—believe that this is monumentally stupid. France's reserves will stop the Wehrmacht's Panzer forces dead in their tracks—or worse, lure them into a huge trap and destroy them at their leisure. The only thing stopping the French Army's massive (albeit non-motorized) regular forces from doing much the same would be speed. And no modern army could survive for long with such constricted lines of supply. In effect they say it is a fool's mission, and waste no time telling Hitler and his "new guard."

But, fool's mission though it should have been, it works. This is a result of the way France designed, organized, and deployed her forces in general terms and with specific regards to the plan they are implementing (moving into Belgium to defend it with a few solid lines of defence). The French forces engaged there have held far too few units back as a strategic reserve, which would be fine if they were facing an enemy offensive on a (relatively) broad front—but not one so insanely narrow and concentrated. The organization of France's military also does not help—France has more tanks than Germany, but very few dedicated tank units. Instead, France's large number of well-armored tanks are dispersed throughout their regular infantry divisions and move at speeds to match, all part of their strategy of defending and advancing on broad fronts. Most of the Armée de l'Air's planes are either obsolete or unserviceable, meaning they are outnumbered and outclassed by the Luftwaffe despite their numerical superiority on paper. The French armed forces also have too little communications equipment; most of the stuff they do have is of poor quality and has too few operators to match—meaning that it takes French officers longer than their German counterparts to receive, pass on, and implement new information and new orders.note . But perhaps more importantly, the French don't have a plan to counter the German one and have a very hard time improvising a solution. A fatal combination of flawed military doctrine and politicking has led to a critical failure of operational planning. The failure to devise contingency plans for the overall "Battle of France" and French doctrine's low emphasis on lower-level initiative and ad-hoc measures means that it's very difficult for the French Army to respond on-the-fly. Essentially, German improvisation and movement has outwitted France's ponderous brawn.

What happens is that, as planned, all of Germany's mobile forces lead a rush through the Ardennes Forest (the French thought it impossible to get that many tanks through and adequately-supplied over such poor terrain with such little trace, and it was admittedly difficult) and make a mad, frenzied dash to the English Channel before the French reserves or regular forces can catch up with them in detail, with as many battle-ready regular troops as Germany can spare following in their wake. France's commanders are too slow to react, and a 'very' large portion of the French Army (plus the Belgian Army and British Expeditionary Force) is cut off in Belgium with few supplies (the idea had been that they would move up to establish a forward perimeter first, and their supplies would follow). Hitler orders his Panzers to stop short of totally destroying the BEF, believing he can cut a deal with Britain, allowing the Royal Navy to evacuate the BEF (the "miracle of Dunkerque", though Dunkirk was just one of the many evacuations that happened at the time) and a sizeable number of French troops as well, albeit with the loss of most of their weapons and all of their vehicles. So the BEF lives to fight another day and France gains the nucleus of a "Free French" army in exile. However, as Churchill himself puts it, "Wars are not won by evacuations." The Allies have still suffered a catastrophic defeat.

The triumphant German army then turns north and crushes—or forces the surrender—of what pockets remain of the entrapped French Army. In seemingly no time at all, they've solved their supply problems by linking up their forces and continue to overrun what badly-outnumbered and increasingly isolated French forces remain to the south. The whole campaign only takes about six weeks, but the Germans take heavy casualties in the process—much as you'd expect, given their less well-equipped and numerous, but much better coordinated and applied forces. As France collapses, Benito Mussolini decides to imitate his buddy Hitler and attack France too. The Italian army does badly despite greatly outnumbering the French, a sign of things to come for Germany's worse-than-useless ally. Nevertheless, after the dust settles, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France have all fallen to the Axis Powers. Hitler makes a point of it to sign France's surrender in the same railway car and in the same forest where Germany signed the armistice at the end of World War I (and even makes the same gesture of leaving during the negotiations as Marshal Foch had done). Celebrations break out across Germany and the population is driven into a euphoric war fever.

The fall of France can be better understood if one notes the near-total collapse of French morale that came with the encirclement and then destruction of the Belgian pocket; with this one stunning strategic victory French defeat was certain, and her soldiers knew this all too well. Whereas Germany's forces were on a morale-high after the conquest of Poland—backed up by a culture of gung-ho militaristic Revanchism that had characterized pre-WWI French culture—France's post-WWI culture was marked by its rejection of all that in favour of a kind of cynical (if not fatalistic) pacifism. Thus, when it was clear that France had lost, many of her soldiers (wisely) legged it rather than die pointlessly—and her leadership looked for a way to end the war on the least harsh terms possible under the circumstances, i.e. as quickly as possible while the Germans' terms were still kinda acceptablenote . As this happens, the German U-boat flotillas begin relocating to the ports on France's western coastline, giving them a clear and open window into the North Atlantic.

Britain therefore quietly seizes the French ships that had taken refuge from the fall of France in Plymouth and Portsmouth, and issues ultimata to the French flotillas in Alexandria and Mers-el-Kébir: surrender or be destroyed. The Alexandrian flotilla of one battleship and four cruisers does not surrender but promises to sit out the war, which the Royal Navy reckons is good enough. But Admiral Darlan's flotilla of four battleships and six destroyers refuses either to surrender or make any promises to their former allies, and so the Royal Navy reluctantly uses carrier-based aircraft and the guns of three capital ships to try to sink the fleet at its moorings in Mers-el-Kébir. The attack on Mers-el-Kébir doesn't do much damage, but it sends a powerful message to the Axis and the Commonwealth that Britain will fight the war to the end, no matter what. More importantly, the Germans keep their word to France and let them keep what remains of the French Navy—three (damaged) battleships, and a handful of cruisers and destroyers. Much of the captured French fleet goes on to be used by the "Free French" forces under General Charles de Gaulle, the Alexandrian flotilla that rejoins the war in 1943.

Apart from India, Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, and a couple dozen other protectorates and colonies Britain stands alone against the relative might of Hitler's Third Reich, and Mussolini's Fascist Italy. Their army is shattered and in no condition to resist an invasion, but they still have the Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force and the English Channel to protect them. The Germans, however, have a problem: the Kriegsmarine, already relatively tiny, took significant losses invading Norway. They also lack specialized landing forces or amphibious landing gear, and their failure to seize the French fleet means it will be a long time before they can be reinforced.note Aerial superiority, therefore, is essential to shepherd an invasion force across the Channel and protect their supply convoys afterwards. Fortunately for the British, the Luftwaffe is exhausted by the high-tempo close air support operations which Bewegungskrieg operations require, so the Germans must pause for several weeks to rest and reequip their air forces before a full-scale assault can begin.

The Luftwaffe does its best to put pressure on the RAF by targeting its aerodromes and radar installations. However, Nazi leadership once again insists upon meddling in the Luftwaffe's affairs, forcing changes in tactics and targets at the first signs of resistance in order to keep the "victories" coming. Bombing priorities are switched between RAF airfields and British urban-industrial centers at critical moments, and they fail to appreciate—largely as a result of false intelligence reports, mind—the significance of radar installations in drastically increasing the RAF's operational and tactical efficiency. This was because British intelligence, lead by William Stephenson, code name:Intrepid, had created the Doublecross system where any captured German spies (And post-war analysis realized that the British caught all the agents!) were forced to choose to become double agents or face execution. As a result of this effective counterespionage, Luftwaffe commanders had claimed that they would be able to reduce the RAF's capabilities to the point that an invasion would be a possibility within as little as two weeks; but after three months of trying for multiple objectives (destroying the RAF, destroying Britain's industry, and destroying civilian morale through attacks on urban centers) they still haven't gotten anywhere, and they've taken an awful lot of losses. The Germans decide to take their strategic bombing campaigns down several notches, making them purely night-time affairs to avoid further losses.

Operation Sea Lion (which was never taken all that seriously to begin with) note is suspended pending the acquisition of sufficient Lebensraum and industry to produce a massive surface fleet—the minimum time-frame for which is five years, hopefully. Many come to believe, in retrospect, PM Churchill's claim that this was the UK's finest hour. Still, the Germans remain the masters of Fortress Europe and the Allies just don't have the strength to defeat them… and Britain isn't off the hook just yet, what with the Nazis taking submarine-based commerce-raiding warfare to new heights. Britain has to ship half of her food supplies and virtually all her rare materials in across the Atlantic Ocean, and there's an awful lot of water out there for the Kriegsmarine's "wolfpacks" to hide in. A constant menace, they destroy thousands of tons of vital merchant shipping, and in just a brief window from June until October of 1940, U-boats sink an astounding 270 Allied ships.

In May 1941, the Germans complete their flagship, the battleship Bismarck. They send her out into the Atlantic to raid commerce because the Germans do not have the numbers to take on the Royal Navy. The British quickly get wind of this and dispatch a squadron composed of battlecruiser HMS Hood and the brand new and untried battleship HMS Prince Of Wales to intercept.note . But Hood is an old ship, designed before the WWI battle of Jutland convincingly demonstrated the vulnerability of battlecruisers, and she quickly explodes under Bismarck's accurate gunfire during their encounter in the Denmark Strait, taking all but three of her nearly 1500 man crew with her.

Shocked, and yearning for revenge, Churchill personally orders anything that can float or fly to hunt down Bismarck. Damaged by Prince of Wales during their battle, the Germans decide to return to the safety of France and successfully give their pursuers the slip, causing the British Admiralty many sleepless hours until Bismarck can be located again. Realizing that Bismarck is already safely beyond interception unless it can somehow be slowed, the British launch (from the "lucky" HMS Ark Royal aircraft carrier) a last ditch aerial torpedo attack using outdated biplanes flown by inexperienced pilots in appalling weather conditions. Fortunately, with the weather working in their favor, the biplanes prove impossible to hit and their squadron leader scores the lucky torpedo hit that jams Bismarck's rudders into a turning action and allows the Royal Navy to catch up. Bismarck goes down fighting and like a certain ship that also went down on her maiden voyage, becomes a legend. Ironically, the U-boats sent to "help" Bismarck only succeed in scaring off the British ships, leaving most of her crew to join Hood's at the bottom of the Atlantic.

At the same time, Britain found itself in a strange situation when Hitler's right-hand man, Deputy Fuehrer Rudolf Hess, made an unauthorized flight to the UK and parachuted in to present a peace proposal on his own initiative to the British government. As it was, the British government, who of course never took his offer seriously, took him prisoner for the rest of his life and found him a headache to deal with considering Stalin was convinced that the silly incident was evidence of the Western Allies plotting with the Axis against him. As for Hitler, he was deeply troubled by Hess' foolhardy stunt, released an official disavowal of Hess' actions and had Goebbels' propaganda machine paint Hess as a total flake for the public. In addition, contrary to the popular image of the Third Reich being obsessed by the supernatural, Hitler had many psychics, astrologers, faith healers and the like on June 9th rounded up as scapegoats for the embarrassment.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the United States—still isolationist but not wanting a repeat of the conditions that pulled them into World War One—declares a state of "armed neutrality" and a resolution to defend neutral shipping on their side of the pond. This effectively results in a state of undeclared war between the U.S. Navy and the Kriegsmarine. Deeply disturbing for the Imperial Japanese Navy is the announcement of a huge naval construction program to make that defence possible—the "Two Ocean Navy" act of 1940 would see it dwarf even the Royal Navy within ten years note . This comes as a tremendous shock to the Japanese, who had long chafed under the hated 5-5-3 battleship ratio: the Two Ocean Navy Act effectively set the new ratio at five to one, with similar increases in other classes of warships and 10,000 additional aircraft. In all their fulminations against the hated treatiesnote they'd never considered that they also served as a check on American behavior.

This rearming also allows the U.S. an opportunity to "loan" 50 aging but still serviceable destroyers to the UK, in return for long-term leases on naval bases, a sale in all but name. The "loaning" continued with the Lend-Lease Act of 1941, which throws the government's support behind the production of massive quantities of armaments for sale to the embattled European powers. But this isn't mere war-profiteering, unlike the earlier "Cash-and-Carry" Act, which was technically open to all belligerentsnote . This offer is open to the Allies only, and Great Britain in particular. It features decent prices and jaw-droppingly huge low- (and some no-) interest loans so that the Allies can actually afford to keep fighting, and more importantly to buy the U.S.'s armaments.note . The U.S. also starts subsidizing airfield construction across the South Pacific with large gifts of cash and construction equipment to Australia and New Zealand, hoping to preserve a lifeline to the Philippines. Taken together, these measures mean the United States's neutrality is now a mere pretense.

Mussolini feels left out of all this conquest, so he decides to try and jump in. Shortly before the fall of France, things kick off when British troops in Egypt (garrisoned to protect the Suez Canal) under the command of General Archibald Wavell launch raids into the Italian colony of Libya. The Italians respond in kind. Initially, things look like they might go well for Mussolini. The Italian military has a massive numerical advantage over the local Allied forces—which grows even greater after the fall of France—and they possess a formidable surface Navy that looks like it can actually wrestle with the Royal Navy and defeat them locally. In addition, their air force is more sophisticated and advanced than the Luftwaffe in many ways (as befitting their roles as aerial pioneers).

However, underneath this apparent strength lies many weaknesses. Mussolini has turned one of the most formidable militaries on the planet during WWI into a paper tiger. He expanded the military to the point where it became unwieldy and could not provide adequate training to all its troops, while technologically, it slunk well below the cutting edge. Italy's fleet of battleships, while formidable on paper, is immobilized both by lack of fuel and fear of losing them. Italy's industry, resources, and economy are nowhere near strong enough to stand up to the rigors of a world war, even had they been mobilized (which they never were anyway). And finally, Mussolini's agenda meant that he made enemies unnecessarily—especially ones that would prove too difficult for him to chew. Unfortunately for Italy, his previous targets had been too weak to contest him effectively. So, ignorant of the pitfalls, he decides to charge right ahead.

In August, Mussolini opts to escalate the campaign and orders the Libyan forces—led by General Rodolfo Graziani—to launch an attack into Egypt to take the Suez Canal, against the General's protests that his forces aren't properly equipped. Not long afterwards, the Italian army launches attacks along the borders they have with the British colonies of British Somaliland, Sudan and Egypt, pitting somewhere around 400,000 soldiers against less than 100,000 Allied troops. Outnumbering the British by around 6 to 1 on the Libya-Egypt front, Graziani drives deep into Egypt while the British commanders scramble to reorganize their forces in the face of generalized attacks against them stretching from the Western desert to the Sudan.

Within a matter of days, Graziani reaches and stops at Sidi Barrani due to supply problems while his compatriots overrun British Somalilandnote and seize sizeable chunks of Egyptian and Sudanese borderland—to the point where Il Duce engages in (possibly exaggerated) Evil Gloating by claiming he has seized territory equal to the British "Home Islands" in the Horn of Africa. However, although horrendously outnumbered and initially outgunned, the Allied forces are able to engage in model fighting retreats that save the overwhelming majority of their forces and inflict far heavier losses than they take. When the overstretched and poorly tended Italian supply lines snap, it only gets worse. Unable to advance or withdraw, the Italians dig in to try and consolidate their gains. They establish a series of fortified camps, stockpiling supplies in anticipation of a renewed offensive to take Alexandria and the Suez.

But before they get the chance to do so the British launch Operation Compass—which was meant to be a 5-day raid by some of the 40,000 Commonwealth troops to weaken the Italians' force of 130,000 soldiers before the latter launch their next offensive. It succeeds beyond their wildest expectations, due to the Italians' chronic lack of communications equipment and staff, and general disorganisation and command-confusion. The inferiority of Italian equipment note , their lack of motorized transports and the highly dispersed nature of their camps meant that individual force after individual force of Italians is surrounded by much bigger and better-equipped forces with its members required to choose between being massacred or surrendering. The British capture virtually all the camps, huge stockpiles of supplies, and tens of thousands of Italian soldiers for less than 700 casualties. The Italians execute a disorganized retreat back to Libya as the ever-advancing British vanguard leads Compass through a localized counteroffensive into a full-blown offensive that continues to drive the Italians westward.

While this is going on, Mussolini decides to divert even more troops to his Albanian protectorate and issues an ultimatum to General Metaxas' (quasi-Fascist!) note Greek government: renounce the British guarantee of their neutrality and allow Italian and German soldiers to occupy undisclosed points of the country. When this is unsurprisingly refused, Mussolini claims that Greece holds an un-neutral attitude against the Axis. The Italians promptly invade Greece across the mountainous border with Albania during late 1940, forcing General Metaxas' military dictatorship into the Western Allied camp.

What follows is a series of Curb Stomp Battles on every front. The British push into Libya, culminating in the encirclement of the Italian Tenth Army (about half of the Italian force in North Africa) near the town of Beda Fomm, where they are eventually forced to surrender en masse despite increasingly desperate and fiercely-fought breakthrough attempts using their new and improved M13/40 tanks… which aren't enough to compensate for the way the Italian army fundamentally lacks the communications equipment and staff they need to actually exploit such breakthroughs (even after the issues of who exactly is in charge and who is supposed to be obeying whom are largely sorted out). After all is said and done, by the end of February 1940 the British have taken most of eastern Libya and captured 130,000 Italian soldiers, several hundred vehicles and over a thousand artillery pieces. In doing so they have given the Allies their first major victory of the war and an invaluable morale boost given the litany of defeats they suffered beforehand.

In East Africa, the British take charge of an Allied force—consisting of themselves, much of the Commonwealth, the 'Free French' rebels and Belgians—and begin to push back into Italian East Africa. Resistance is considerably sterner than in the North; the overextended Italian positions crumble but don't go down without a fight in the mountainous terrain. However, even with their superior numbers, the poorer quality of their troops and Command&Control links slowly tell out while Ethiopia erupts beneath their feet. The Italians turn and fight numerous hard actionsnote , but the clock is ticking and they are running out of room and ammunition.

Meanwhile, Churchill's French friend, Charles de Gaulle, is not sitting idle. French North Africa submitted to Vichy control and many French troops that escaped with the British at Dunkirk opted to return to Vichy France in exchange for amnesty as the war got worse for the Allies. But the General is able to find financial support, weapons, and recruits in the colonies of Central Africa. After the thrashing of the Italians in Operation Compass, Félix Éboué, governor of Chad, writes to de Gaulle expressing his desire to align with the general and the Allied powers. Within a month and a half of exchanging notes, Chad joins de Gaulle's struggle, Cameroon's colonial government is toppled by de Gaulle's number two general Philip Leclerc, and the French Congo and Ubangi-Shari (present day Central African Republic) join this movement. Together, these colonies formed Free French Africa and suddenly the Nazis can't so easily portray Charles and his Free French Army as toothless to their Vichy subjects. Félix uses his power to enact colonial reforms whereby African traditions will be respected and working conditions will be improved, but French law will continue to be the basis of government. The British use their colonial assets to expand the roads, ports and airports for the war effort.note By 1943, Free French Africa raises and trains 7,000 colonial soldiers- many of whom will distinguish themselves in the North Africa theater. They will contribute 20,000 troops by the war's end. The colonial governments also contribute financially to the Free French war effort through taxation, loans and trade, allowing Britain and de Gaulle to finance the still nascent French Resistance.

Meanwhile, the ill-prepared Italian invasion of Greece stalls and then is routed by the woefully outnumbered Greeks utilizing superior leadership, the terrain, and Allied aid. The Greeks pursue them into Albania itself and over the course of several bitter months of fighting, hold the much larger Italian force there. Simultaneously, the Regia Aeronautica's attempts to bomb Malta into submission fail, and the naval war in the Mediterranean turns sharply against them with a series of battles, most notably those of Tarantonote and Cape Matapannote . It seems like a perfect sweep.

Nonetheless, while the Western Allies have won a series of victories they have not even come close to driving the Italians out of anywhere yet. This gives the Italians time to regroup, rearm, and reinforce. The Germans, who had until now been content to let the Italians get on with their own foolish endeavors, fear that Mussolini's domestic support is not so firm that he can weather the loss of north Africa and hear that British reinforcements are being sent to Greece. The German military had already advised Hitler of the wisdom of ensuring Greece's neutrality (if not outright befriending them) at all costs, since Greece's proximity to Romania means that the Commonwealth can use Greek airfields to bomb Romania's oilfields—German's primary source of petrol. Hitler is already engaging in a buildup of forces for a little trip to Moscow, and any disruption to that fuel supply will cripple his plans. Germany's only alternatives are mind-bogglingly expensive coal-derived synethetic petrol, highway-robbery-priced Soviet petrol, and minuscule amounts of Hungarian petrol. Driven by military necessity, and with a great deal of annoyance at Mussolini's utter lack of strategic thinking, Hitler accepts that Germany must intervene on both fronts.

In response, Germany sends a hundred thousand combat troops, including two Panzer divisions, to conquer Greece and Yugoslavia note and one division to North Africa to shore up the Italian defences there. At the time a 'corps'/'Korps' is generally understood to consist of two-to-three 'divisions' (c.15k combat troops each), so designating the German expeditionary force to North Africa the Deutsches Afrikakorps is a bit of a grandiose gesture. However, it is a deliberate gesture to help foster the impression that Germany has actually dispatched far more troops and tanks (45k and 600) to north Africa than it really has (15k and 200). The 'Korps' is led by the newly promoted Major General Erwin Rommel note .

Annoyingly for the Wehrmacht, Yugoslavia suffers a British-backed coup which sees her leave the Axis. When Bulgaria refuses to allow German troops military access (so they can invade Greece), Germany marshals her troops in Austria and Hungary before declaring war on Yugoslavia and then—once they reach the Greek border—Greece. Churchill overrides the British military to take the militarily/logically/common-sensically questionable but politically important step of stripping their army in Egypt of troops in order to reinforce Greece, only to be utterly defeated in their third hasty and incomplete evacuation of the war. The Germans utilise a full hundred thousand combat troops for this purpose, including two Panzer divisions (400 Panzers, 30k troops). The awful condition of the Greek road network and the relatively long distances traversed mean that these divisions will only finish their refitting and repairs in the German factories wherein they were made in August 1941 (neither Germany nor anyone else has come up with the idea of trying to effect anything but extremely minor repairs to tanks 'in the field'/'at the front' yet). Since Germany only has 350k mobile troops and 3.6k tanks (including these two divisions and the one in Africa), their absence will make the coming German invasion of the Soviet Union ever so slightly more impossible than it already is (given just how woeful the plans for making this happen are).

The Germans take the island of Crete with 3000 troops from its more than 10,000 defenders in the world's first major airborne assault, though the extremely high casualties discourage them from ever launching another like it. Ironically the British, and later the Americans, are very impressed by the performance of the Fallschirmjäger and soon issue directives to begin building up their own airborne divisions. Only the plucky island of Malta manages to hold on despite heavy casualties and near-starvation, an act that gets the entire island awarded the George Cross. Mussolini is humiliated, and Hitler is provided with a whole raft of snide remarks for future cocktail party conversations (it's worth noting that Italy suffered nearly as much as France in World War One, so the Allies weren't the only ones suffering from fatalism and defeatism). The field shifts to North Africa, where the Axis and Allies wage battles for control over the vital Suez Canal and access to the priceless oil supplies of the Middle East.

Rommel arrives in Tripoli on February 14, 1941, to begin supervising the offloading of his new command, and finds himself in charge of just one Panzer division (14,000 combat troops and 200 tanks) with strict orders to help the (80,000) Italians conduct a mobile defense of Benghazi and Tripoli because the total lack of railroads means that operations more than 200km from those ports will be costly or even fatal to his supply truck fleet of 6000 (not including 2000 within the division itself). But do those orders and the physical impracticality of defying them stop him? Nope. What happens next is rather bad for Germany's overall war effort, though not to the extent of actually costing her victory in the coming Soviet-German War. However it certainly is very eye-catching and impressive, making for good headlines and propaganda —especially considering that at the time, very little else is happening bar some ineffectual air-raids and the navy's drama with the Bismarck.