This section covers the war with Japan, starting with the Second Sino-Japanese War. In summary:

- In 1937 an undeclared war breaks out in China, against the wishes of Chiang Kai-shek and most elements of the Empire's Army and government. The Soviet Union immediately begins supplying the Guomindang with credit, machine tools, arms, ammunition, equipment, military and technical advisors, and volunteers through Chinese Mongolia. But to the immense frustration of Chiang Kai-Shek, Yan Xishan (warlord of Shanxi province, where Soviet aid enters the Guomindang's rail-network) gives up his home-turf without a fight - forcing Soviet aid to take the long way around through the warlord-fiefdoms of Xinjiang & Qinghai, drastically reducing the tonnage delivered. The battles for the southern North China Plain and Lower Yangzi go badly for the Guomindang, who lose the entirety of both regions despite a much-touted tactical victory by Guomindang forces at Taierzhuang. In the course of this Chiang has the dikes of the Yellow River blown to prevent the retreat from northern China from becoming an encirclement or a rout, halting Japanese operations on the North China Plain for 3 months but causing some 2 million civilians to die from water-borne and starvation-related diseases. The Guomindang finally halts the string of Japanese offenses with an ingenious combination of regular and asymmetric warfarenote , the ultimate result being strategic stalemate. Neither Chiang nor Tokyo can agree on peace conditions. Soviet aid continues as Japan being bogged down in a Forever War suits them just fine and the Soviets badly need the experience for their pilots, who saw relatively little action in World War Inote .

- In 1939, after the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the Red Army's victory in the Nomonhan/Khalkhin Gol border-battles in Soviet-allied Mongolia, a Soviet-Japanese Non-Aggression Pact is signed. Soviet aid to the Guomindang dries up as Stalin gives full priority to The Red Army's modernisation program (in anticipation of a European War in the next five years with NSDAP Germany). Red Army Air Force planes & pilots, and technical & military advisors remain, but Soviet material aid (spare parts for tanks and artillery, petrol, etc) gradually dries up. Siberian and Manchurian forces remain facing each other across the border, but Japanese reserves and most freshly-created forces are free to campaign against the Guomindang. Wang Jingwei, leader of the Guomindang's left-wing, can't stomach any more of what he sees as pointless bloodshed and leads a splinter faction of the Guomindang to negotiate with Japan. To his chagrin, his peace-minded contacts in the IJA and Imperial Government are defeated in a bout of internal politicking which sees the rise of General Tojo Hideki to the Prime Ministership. Wang finds himself leading a rubber-stamp government. Meanwhile, the USA starts subsidizing airfield construction across the Pacific with large gifts of money and construction equipment to Australia and New Zealand, hoping to safeguard their supply lines to the Philippines.

- In 1941, the Guomindang is on the verge of total defeat with the (poor, rural, and flooded with tens of millions of refugees that have increased their population by as much as a third) provinces under its control essentially being slowly starved out by the Japanese, its forces' ammunition reserves at critical levels, and inflation mounting. At Stalin's urging the Chinese Communist Party breaks its truce with Japan for a few months to attack Japanese forces bordering the Yan'an Soviet in Shanxi province and Inner (Chinese) Mongolia, but after the People's Liberation Army is routed with heavy casualties Mao's faction uses the defeat to discredit those party leaders loyal to Moscow and thus consolidate his grip over the party. Mao goes on to forbid any action against the Japanese. The Free Guomindang will disintegrate or be torn apart within two years at best, just a few months at worst.

- By late 1941 Soviet aid dries up completely as all Soviet pilots, aeroplanes, and advisors are recalled to defend The Motherland from Germany's Operation Barbarossa. The IJA contemplates aiding Germany in her invasion of the USSR, but a July conference rules it out as their pre-war assessments (that the USSR would win) seem to be confirmed during that month's battle at Smolensk. Japan's Grand Strategy of State-Building for the Wang Jingwei régime and Containment of Chiang's Guomindang is on the verge of success, but the seizure of French Indochinanote gives the United States under President Roosevelt a reason to impose sanctions on Japan in the name of bringing her back to the negotiating table with the Guomindang. The embargo is on iron and oil, the latter of which Japan's dysfunctional junta has had neither the time, foresight, nor money to stockpile in large amountsnote . In a spectacular illustration of the Sunk Cost Fallacy, in December 1941 the junta implements the IJN's Attack Plan South to seize British Malaya and The Dutch East Indies. In a pique of extreme paranoia, they assume that the USA would respond to this by declaring war on them in defence of The Allies, and so attack the USA (without formally declaring war) at the same time so that they can maximise their initial strategic advantage and hopefully negotiate some sort of peace with everyone that involves them keeping China. Or something. The USA's forces in The Pacific are largely unprepared for the conflict, though not 'surprised' per se; US forces were already in the Phillipines and considered that area more likely for an eventual attack, and while the USA recognised an Allied-Japanese conflict as a real possibility they had never considered that the Japanese would attack them as wellnote .

- 1941-2 Attack Plan South succeeds beyond the Navy's wildest dreams, but the IJA's strangehold on the Guomindang is inadvertently lost due to life-saving US loans and the diversion of IJA resources away from actions against the Guomindang. By early 1942 the front has stabilised in northern Burma, where the British asked the Guomindang for troops to help British and Indian forces defend the colony. The Guomindang sends all it can spare, including their only motorised division, but the Anglo-Chinese force is forced to retreat to northern Burma. Joseph Stilwell is given command of said Guomindang forces as a publicity stunt to capitalize on pro-Chinese sentiment within the USAnote . The loss of Burma means a loss of 10% of the Indian Subcontinent's total grain supply, though the loss hits Bengal hardest - some two million die of starvation-related diseases before Britain overrules the regional governments and imposes a comprehensive program of famine-relief. Likewise, the 'Henan Salient' of Free China suffers its worst famine in a hundred years. The Guomindang has no money or food to spare for relief efforts, and two million or so die of starvation-related diseases. By mid-1942 the other fronts stabilise in Australian New Guinea and the mid-Pacific. The 'back' of the IJN is broken at the Battle of Midway wherein its biggest aircraft carriers (and best airmen) are destroyed with minimal USN losses. The losses are devastating - Japan could not hope to replace the highly specialised ships and planes she has lost in five years, but the USA produces the same number of both in just one. The loss of experienced airmen is also critical; the Japanese suffer from a lack of knowledgable instructors (anyone who is any good tends to be sent to the front lines to try and help), and thus is forced to send pilots who are little more than trainees into battle. The USA, on the other hand, routinely rotates it's experienced pilots back home to serve as instructors, giving freshly graduated rookie pilots a massive advantage when they first go into combat.

- The USN uses small numbersnote of amphibious troops to 'island hop' westwards from Midway Island and cut Japan off from her oil supplies in south-east Asia. Starting on the 20th of October 1944, General MacArthur's plan to re-take the Philippines is implemented, and in the ensuing Battle of the Leyte Gulf virtually the entire IJN is annihilated with minimal USN losses. The loss of the entire fleet does not escape The IJA and Japan's civilian population, moreover, who both realise that news of another great victory is a whopping great lie and that their defeat is at hand. With the Philippines secured and the IJN gone, Japan's supply of south-east asian raw materials (including food) is cut off and the USA's strategic bombing campaign begins. More specifically, almost none of the Jutenote and grain that the IJA had hoped to export from Vietnam makes it to Japan - a cold comfort for the two million or so Viets who die in the ensuing Gulf Of Tonkin Faminenote . The planned Burma Offensive to restore the land-link to the Guomindangnote is disrupted by the IJA's U-Go offensive against the Sino-British forces in northern Burma and the Guomindang-Warlord forces in General Long Yun's Yunnan.

- In early-mid 1944, the IJA U-Go offensive is met by Sino-British forces, with General William Slim's 'Forgotten Army' stopping the Japanese advance at the simultaneous battles of Kohima and Imphal, sometimes referred to as 'the Stalingrad of the East' (in terms of being a critical turning point rather than in terms of racking up similar casualties). Preventing Japan's advance into British India proper (Imphal was in Manipur, near India's North-Eastern border), it proved to be the most costly defeat the Japanese had suffered to that date, with starvation, disease, and exhaustion taking a critical toll on their retreat through Burma.

- In mid-late 1944 the IJA launches Operation Ichi-Go to capture the Chinese airbases the USA is using to bomb Japan and improve its logistical situation across mainland Asia by making an overland supply route available from Korea down to Rangoon. It doesn't work, but it hamstrings the Guomindang and the companion 'U-Go' offensive in Burma delays the Allies' Burma Offensive a little, though the Allies still manage to take Rangoon before the Monsoon arrives in earnest. Meanwhile, Mao's Chinese Communist Party maintains its truce with the IJA and sneaks massive forces past the Japanese lines to crush Guomindang-holdouts and partisan base areas right across the Japanese-'occupied'note North China Plain, replacing them with their own Socialist Communes (Soviets) while the Japanese are busy trying to crush the Guomindang.

- In 1945 the USA's forces are massing on Iwo Jima and the Ryukyus, ready to launch Operation Downfall later in the year (or in 1946). The Japanese economy is at a standstill as famine looms. To avoid the mutual butchery that could result from Operation Downfall, the U.S. drops the first of their newly developed atomic bombs on Hiroshima on August 6th, provoking the Supreme War Council, the de facto Imperial Japanese high command, to begin an emergency meeting discussing the sudden disappearance of Hiroshima, a communications hub, and all lines that went through it. While Japanese High Command is aware from the outset the most likely culprit was a nuclear weapon, General Amami, head of the still-dogmatic "war faction" casts doubt on the veracity of the claimed "weapon of unparalleled destructiveness" and stalls by ordering a team led by Dr. Yoshio Nishina, the foremost expert on nuclear physics in Japan, to examine the area and identify the nature of the bombing that suddenly wiped out all communications in the area. Dr. Yoshio quickly confirms the usage of a nuclear weapon and sends back a haunting report on August 8th. Despite this, the war faction is not moved. From their own experiences with a nuclear weapons programme, they believe even the United States would be hard pressed to build a single bomb, and that more would be an impossibility. Prime Minister Togo's peace faction however, grows increasingly desperate, as they (as it turns out, rightly) believe more nuclear weapons are on the way.

- Acting upon his commitments at the Yalta Conference (that the USSR would help liberate the occupied territories of mainland East Asia within three months of the end of the war in Europe), Stalin orders the Red Army to perform the "Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation", which it does on August 8th, one day from the deadline set on the nineth by Germany's surrender on May 9thnote . The Red Army had been building up the invasion force even before the end of the western front and with the 2+ million war-hardened mechanised columns of the Red Army and their Mongolian auxiliaries, quickly overran the exhausted and lightly equipped 1.5 million IJA troops. In response, High Command once again calls a meeting on August 9th, this one focused entirely on the invasion of Manchuria. Despite this, the meeting on August 9th marks no shift in the position of either the Peace or War factions as the meeting concludes at around 6 PM, despite the imminent threat of invasion from two directions at once, with the Red Army poised to invade and having a good chance of taking Hokkaido.

- Later the same day, on August 9th the USA drops a second atomic bomb upon Nagasaki, shocking the war faction and even Emperor Hirohito himself, who breaks the deadlock, and declares his intention to announce his surrender to the United States, in light of the "new and most cruel bomb" of "incalcuable" destructive power, which had now been proven not to be an one-off. The pro-war members of High Command are cowed, but not all of Japan. The still-defiant IJA continues to fight on in mainland China while several junior officers instigate the "Kyujo Incident", an attempted coup just before the announcement of unconditional surrender. Nontheless, Hirohito begins his speech as planned on the 15th, a mere half week before the planned third atomic bomb would have struck Tokyo itself. American forces back off from Operation Downfall. The Second World War, is at last over.*

The superiority of Japanese equipment, training, unit organization, and command structure—not to mention air power, which is being used to level Chinese towns and cities more or less with impunity (typically by firebombing)—has counted for nothing in the face of China's vast size and massive population. For instance, the Chinese have barely any antitank weapons, but the Japanese have barely any tanks in working order that they can bring to where they are needed, except in the on-and-off meat grinder battles which rage through the hills of southern and central China. In a relatively unmolested, rural, and mountainous province of north-central China, a young Communist official is slowly offing his rivals and building up a power base for himself. He eventually becomes the leader of the socialist commune there, the largest in the country, and uses his clout as a warlord to secure his appointment as chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. His name is Mao Zedong (aka Mao Tse-tung).

Though the Guomindang has been working hard to promote the image of stalemate, Japan is winning. Even though the Guomindang managed to relocate all their factories to the mid-Yangtze around Changsha and the upper Yangtze basin around Chongqing, it just isn't enough. China is an overwhelmingly rural and agricultural economy, and the Guomindang has been trying to fight a modern war (against a modern, industrialized nation-state) for four years now while only holding onto a small part of it. Jiang's control, moreover, is slipping—with his most loyal forces decimated at Shanghai and in the battles for the lower Yangtze, the uneasy balance of power between him and his warlord "allies" at the regional and local levels has changed decisively in their favor. What's more, for four years now Jiang's avowed strategy has been one of "trading space for time"—but there are places that the Guomindang simply cannot afford to lose (like Chongqing, Jiang's wartime capital). Moreover, the Guomindang is still dependent on certain supplies from within China (like grain) and the outside world (like artillery). Accordingly, the Imperial Army's strategy has had two aims: blockading the Guomindang and bleeding them dry. This means placing Japanese garrisons right across the occupied territories and waging decisive battles for places like the central Yangtze city of Changsha, eventually the site of four major battles in four separate campaigns over the course of six years.

Although the Guomindang has held on so far, its forces' combat efficiency deteriorates daily. Only a handful of grunts in Jiang's core armies from 1937 are still around, and the Guomindang has exhausted the supply of willing recruits and non-critical people who can be conscripted. The Japanese blockade, too, is almost complete; the "Burma Road" between warlord Long Yun's Yunnan provincenote and British Burma is the Guomindang's only link with the outside world after the Japanese take the ports of south China in ’38-’40 and bully the Vichy régime into giving them French Indochina.

The internal blockade of Free China from Occupied China has not been going well—Japan just doesn't have the manpower to enforce it outside the cities of the lower Yangtze and coastal China—but this is set to change, as the one-time Guomindang party leader Wang Jingwei (who had been overthrown by Jiang in a military coup) has defected to the Empire. With his help, they have been able to establish their own "independent" Chinese national government based out of Nanjing. The burgeoning Japanese-trained forces of this new régime are freeing up more and more Japanese troops for service further into the interior. In a year, maybe two at the most, the Guomindang will fall.

After the fall of France, Japan took the opportunity to effectively seize the French colony of Indochina—including modern-day Cambodia and Vietnam—as part of their blockade strategy, ostensibly at the "invitation" of the collaborationist Vichy government. Thailand, fully aware of which way the wind is blowing, voluntarily joins the "Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere" and becomes a Japanese client state. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, worried about Japanese expansion in Asia, has been looking for an excuse to act against them for a while now. He manages to get the United States to restrict all steel and oil exports to Japan in an embargo in an attempt to bring them to the negotiating table concerning China. Since the U.S. is Japan's #1 supplier of both essential commodities, the Japanese government is between a rock and a hard place: they cannot be seen as backing down to the U.S., but they don't have the strength to take them on and win. With Holland having fallen to the Germans and Britain preoccupied elsewhere, the Imperial Navy again proposes, for the umpteenth time, their plan to strike south to seize the oil supplies and rich natural resources of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and British Malaya.

This time, however, the Cabinet is willing to listen. The fleet's oil supplies will be depleted within a matter of months, and it's not as though the Navy and its attached ground forces (the Special Naval Landing Forces) have been making a huge contribution to the China theater anyway. Taking on the Dutch means taking on their ally Britain. However, Britain and the U.S. have numerous mutual business and territorial interests in China, such as the British–American Tobacco Company and the (joint-sovereignty) International Settlement at Shanghai. The Navy and the Cabinet know all too well that an imperial(ist) power like the U.S. would never pass up the chance to use Japan's meddling with the U.S.'s affairs, however indirectly, to declare war on them and make them a colony like the Philippines.

However, if they strike first, they might still be able to salvage the China Incident. If they can just give Johnny-foreigner a sufficiently impressive taste of cold steel, Japan's junta convince themselves, then he'll see just how enormously bloody and costly an official War (with a capital W) with Japan would be. After all, to this day the Americans haven't shut up about how many people they lost in the Great Warnote , or in their civil war. Even if it weren't for their lack of "stomach" for real fighting, it's clear that the U.S. is above all a sensible and opportunistic power—the U.S. always looks for the maximum effect for the least effort. A massive war with Japan would be of such limited benefit to them, and could only be won at such great cost, that they would rather back down than fight it. Even if they do declare war on Japan, they won't have the stomach to stick it out to the end—the Russian Empire, which hadn't even been a "mob-rule" democracy like the USA is, had been bested like this in a short war for which they didn't have the stomach.

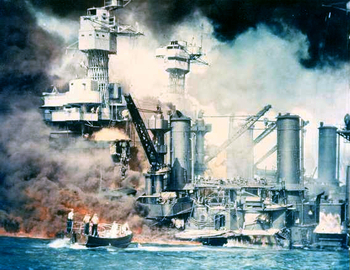

After six months of planning and training under the supervision of Naval Marshal General Isoroku Yamamoto, a task force based around six aircraft carriers moves out under complete secrecy. On Sunday, 7 December 1941, they catch the U.S. Navy's Pacific Fleet completely off guard and at anchor at the Pearl Harbor Naval Base in Hawai‘i. Johnny-foreigner is left reeling from his first taste of cold steel in decades as the Imperial Navy's Most Valiant Air Forces strike a devastating blow against the naval forces of the Most Glorious Empire's New Enemynote .

That said, there isn't much permanent damage. Many of the ships can be—and are—repaired and returned to service within a year or so; only three ships are completely out of commissionnote , and a lot of matériel is salvaged from them, the blessing in disguise of being attacked at anchor in a shallow, friendly harbor; especially critical, none of the American carriers (some of the primary Japanese targets) were in harbor during the attacknote . Ironically, with their battleships out of action, the U.S. Navy is forced to adopt the very same carrier task force concept that the Japanese had just demonstrated so effectively. Though it is not immediately evident to most observers, this move changes naval warfare forever. This incident and the later sinkings of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse by purely air attack without the protection of aircraft carriers' fighters means that the era of the battleship is over—although they will nonetheless see further service in the current conflict.

Though not quite as spectacular at first glance, the Japanese air raid on Pearl Harbor is not nearly as costly to the Americans as their invasion of the Philippine Islands, which had been a U.S. territory since the Spanish-American War. The Americans were in the process of reinforcing the island as part of the massive rearmament and expansion of the U.S. military after FDR's reelection in 1940. FDR promised to keep the U.S. out of the wars overseas, but that didn't mean he wouldn't prepare just in case. However, the American forces defending the Philippines are still woefully underequipped for the task. Upon hearing of the attack in Hawaii, the Philippine and American forces go on alert, with the Far East Air Force scrambling to meet any Japanese attack that might be aimed at them. But when the Japanese do come, they end up overwhelmed, and many of the FEAF's planes are caught while refueling on the groundnote . While the FEAF has received some new planes in the form of B-17 Flying Fortresses and P-40 Warhawks, many of the Philippine and American pilots still fly obsolete planes such as the P-26 Peashooters, with their open cockpits and braced wings. Even so, several Japanese planes meet their end at the hands of these outdated planes, including two Japanese Zeroes, hinting at their critical defensive flaws.

The jungle conditions in the Philippines prove brutal, and the Japanese troops suffer from heatstroke and various tropical diseases. Though they are in no position to capitalize on it, at one point late in the battle this causes American and Philippine forces to outnumber the Japanese two to one. The American forces are pressed back to the Bataan Peninsula, with General Douglas MacArthur commanding from the island fortress of Corregidor—earning him the unflattering nickname of "Dugout Doug". Roosevelt orders that MacArthur, his family and staff be evacuated to Australia, threatening him with a court-martial when the general proves recalcitrant. The general promises "I Shall Return!" Soon after, the American forces on the Philippines surrender, and MacArthur spends most of the war working to advance towards and retake the islands where he has spent much of his career.

At the same time that MacArthur is fighting in the Philippines, the British suffer a one-two punch in China and Malaya. Hong Kong, a Crown Colony since the Opium Wars of the 19th Century, is isolated by the Japanese literally hours after Pearl Harbor is bombed. A British army of 15,000 soldiers is tasked with defending a city as densely populated as London against overwhelming Japanese air and land forces. While the British and their colonial troops put up a stubborn fight, the city is forced to surrender on December 25th and is administered by a Japanese military governor until the war's end.

Churchill is startled by Hong Kong's fall, but not surprised. After all, it was lightly defended and surrounded by the Japanese to begin with. The truly devastating blow to British prestige comes in Malaya. A full British Imperial Army is stationed there, operating out of Singapore, "The Gibraltar of the East". He pins the Allied defensive strategy on Singapore surviving as a thorn in the side of the Japanese until the Commonwealth and the United States can fully mobilize their forces in a counterattack. On paper it's a solid strategy. Over 100,000 British and Australian, Indian, and Malayan soldiers are stationed in Singapore- and they're soon joined by Dutch elements reforming after being pushed out of the Dutch East Indies. Singapore's harbor has heavy naval gun emplacements that can trade fire with Japanese battleships, and the mountain and jungle terrain along the peninsula facilitates a good land based defense. Churchill also dispatches a naval squadron to "show the flag" in the runup to war which includes the battlecruiser HMS Repulse and the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, fresh from its repairs after fighting the Bismarck. A holding action in Malaya could give the Japanese a thorough beating… if the British troops had the time, training, and equipment to fight. Most of the soldiers deployed to Malaya have not engaged in combat with the Germans or Italians in Europe. They have no tanks or armored vehicles, few anti-tank artillery pieces, insufficient rations, outdated aircraft, and the great fortress of Singapore doesn't have any fortifications. And even if the Brits had the supplies to take the fight to the Japanese, the local road system isn't up to supplying a modern army in the Malayan jungles (the Japanese will often famously outflank the British not with trucks, but bicycles on jungle tracks) and the weather conditions sap the troops' strength before they reach the front lines. Oh yeah, and don't forget the poisonous insects, venomous snakes and spiders, and literal man-eating crocodiles that inhabit the jungle.

The Japanese launch the invasion of north Malaya at midnight on the 8th and essentially pull off a D-Day invasion in the dark against British bunkers, barbed wire strewn beaches, and artillery emplacements. The British sink several Japanese transports but the Japanese land most of their troops and force the Commonwealth to retreat. The Naval squadron departs Singapore harbor to try and prevent further Japanese landings, but is soon left without air cover. The Japanese realize their good fortune and launch numerous air attacks from land bases, sinking the Repulse and the Prince of Wales, one of Britain's newest and most advanced battleshipsnote , for the cost of just 4 Japanese bombers. Now the Japanese begin landing masses of troops unopposed. From there, the fighting continues on down the Malay peninsula following a pattern. The British establish a defensive line. The Japanese pull up tanks to engage the Britishnote . The Japanese infantry scatter into the jungle behind the British, surround them, and force them to withdraw further down the peninsula. Civilians hear the fighting and flee toward Singapore. Rinse and repeat for two months until the Japanese are at the gates of Singapore in February. The Commonwealth troops destroy the causeway bridge into the city and breathe a sigh of relief while they quickly reorganize into an ad-hoc defense of Singapore island. They are surrounded, have no incoming resupply, and the city is filled to the brim with hungry troops and starving civilian refugees.

Churchill can't understand why the battle is going so poorly and issues orders for Singapore to be defended to the death by every man, just like the Russians are currently doing at Moscow. The troops that receive this order have not been eating regularly. They have no tanks, no artillery, no aircraft, and are almost out of ammunition. The entire army has been involved in the two month fighting retreat and none of the men are rested- in fact, they're now being tasked with throwing up rapid defenses along the shores of the city. Their one defensive trump card, the naval guns in Singapore harbor, have armor piercing shells in their magazines. Those shells will sink any Japanese battleship. They will only bury themselves in the dirt if fired at ground troops. On February 8th, the Japanese cross into Singapore via armored landing craft and fighting ensues in the outer suburbs. Within a few days, they repair the causeway and bring in their light tanks to seize the city's fresh water reservoir. British General Arthur Percival realizes that the battle is over. There is no way to evacuate his troops and they haven't the strength to fight a prolonged, Moscow-style defense. If Japanese bullets don't kill them, thirst will do the job in 7 days. He surrenders to General Tomoyuki Yamashita on February 15th, 1942. Japanese troops overrun several hospitals during and after the battle, massacring the wounded and raping nurses before executing them as wellnote . 130,000 British Commonwealth and allied troops become prisoners of the Japanese Empire overnight. They will be transported aboard "Hell Ships"![]() to the Japanese home territories where many will be worked to death until the war's end. Churchill's doctor reported that he received the news of Singapore's fall with stunned silence. Months later, he would stare blankly at times and when asked what was troubling him, reply "I cannot get over Singapore." With Rommel still racing around Africa and Britain having just survived the blitz, the battle for the Pacific will have to be fought by the American, Australian, New Zealand, Indian, and Chinese forces. And now Australia and New Zealand appear to be defenseless.

to the Japanese home territories where many will be worked to death until the war's end. Churchill's doctor reported that he received the news of Singapore's fall with stunned silence. Months later, he would stare blankly at times and when asked what was troubling him, reply "I cannot get over Singapore." With Rommel still racing around Africa and Britain having just survived the blitz, the battle for the Pacific will have to be fought by the American, Australian, New Zealand, Indian, and Chinese forces. And now Australia and New Zealand appear to be defenseless.

Of greater concern to the Japanese, though less apparent at the time, is the U.S. Navy's declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare against the Empire of Japan—similar to Germany's submarine campaign against that other island empire, Britain. At first, however, this is a hollow threat—modern submarines are relatively few and far between and overly cautious peacetime skippers and defective torpedoes will limit their effectiveness for months to come. Meanwhile, Japanese submariners, who already have effective torpedoes, squander their initial advantage by concentrating on scouting for their fleet and hunting allied warships instead of merchant vessels. The Japanese obsession with a short decisive war means they'd never developed proper doctrine for commerce warfare. Even if they had, their lack of island bases and the vastness of the Pacific effectively prevent a Japanese submarine campaign against Australia and the U.S.'s western coast to match the German assault against Britain and the U.S. East Coast in the Atlantic. Even worse for the Japanese, this emphasis of the offensive meant little real enthusiasm in the Navy for the Boring, but Practical work of antisubmarine convoy protection of their own shipping until it was too late to stop the American submarines from taking maximum advantage of their negligence.

Tactical success aside, the Navy and the Cabinet soon realize they have made a mistake. This was partly a failure of the Japanese intelligence services, which were weak, but more fundamentally a failure to understand the motivations of their now-enemies. The U.S. wasn't at all interested in helping Britain maintain her Empire, or even using the conflict as a pretext for a war with Japannote . In fact, their "preemptive" offensive has generated huge outrage and calls for revenge among the American public, the attack on the fleet in particular being reviled as "A date which will live in infamy". This makes it possible for President Roosevelt, who personally supported U.S. involvement in the the wider war but previously had to contend with a staunchly antiwar public, to declare war on Japan and bring the U.S. into the Western Allied camp. He also mandates massively increased investment to make the ridiculously large "Two Ocean Navy" (as laid out in 1940) a reality in just three years, stating his intention to take the war to Japan. Rational officers like Admiral Yamamato had understood the nature of the U.S.'s strong isolationist lobby, not to mention its overwhelming material advantagenote . But these officers were duty-bound to follow the government's orders anywaynote .

To compound the looming disaster for the Axis, Hitler promptly commits one of the greatest strategic blunders of all time by declaring war on the United States in support of his ally, despite the fact that he was under no formal obligation to do so, since the Tripartite Pact with Japan stated that Germany would have had to step in only if Japan were attacked first. This clears the way for Roosevelt to have the U.S. join the fight in Europe with complete domestic political supportnote . Thus, as 1941 comes to a close, the Germans, who six months before only faced the British Empire and its Commonwealth, are now at war with the three most powerful non-Axis nations on Earth.

At this point, the defeat of the Axis is inevitable, their poor decision-making having doomed themnote .

But that would not become clear immediately. The combination of the attacks on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Malaya resulted in the Empire of Japan promptly sweeping the Western Allies nearly out of the Pacificnote . Within just a couple of months these are all secured for Japan, and the Japanese sweep outward to take the entire Dutch East Indies and most of Burma. Six months of uninterrupted victories leave Japan the master of East Asia and the Western Pacific.

To raise morale and curb spying, the U.S. promptly herds all its ethnic-Japanese citizens on the west coast into internment camps and expropriates all their assetsnote . The U.S. does, however, allow Japanese–Americans to serve with its armed forces—but only in the European Theater, except for some who serve in noncombat roles as translators. Roosevelt is keen to capitalize on the strength of the American people's anti-Japanese hatred, so he gets Army Chief of Staff George Marshall to assign the U.S. Army to help the Guomindang in their fight against the Imperial Japanese Army. Somewhat cynically, Marshall appoints the newly-promoted General Joseph Stilwell to head up the U.S. Army's Expeditionary Force to China, but doesn't actually give him any men. From the U.S.'s standpoint, it makes no sense to give the Guomindang any more support than necessary for their ally to survive in its role as a meatshield. Besides, the nearly insuperable logistics of even getting supplies overland to China when Japan holds nearly their entire coastline makes it difficult even to do that.

This is more or less exactly what they do, giving the Guomindang only a fraction of the aid they give Britain or the Sovietsnote and turning down Jiang's calls for American troops. Moreover, the Lend-Lease supplies they do send to Jiang are largely consumed by their own forces outside of allowing them to hire American fighter pilots as the formidable mercenary force, The 1st American Volunteer Group aka The Flying Tigers. Stilwell's on-loan Guomindang divisions (in India) get most of the army equipment meant for the Guomindang at large, and Claire Chennault's Far Eastern USAAF group gets much of what does make it to China proper.

The U.S. does, however, give the Guomindang enough money in the form of low- (and some no-)interest loans to keep their government ticking over—for a while. After four years of cripplingly expensive total war, the Guomindang has been forced to decentralize its administration and tax collection to the regional and local level, arbitrarily conscript peasants, and print money in order to survive. The consequences have been mounting governmental corruption and monetary inflation. The loans help stave off the Guomindang's imminent implosion, but it isn't enough to allow them to reform and recentralise. (The huge cash inflow of the loans actually makes the inflation worse.) Consequently, the Guomindang's administrative and fighting efficiency continues slowly but inexorably to deteriorate.

To add onto this, the U.S. is still reeling from the attack on Pearl Harbor, and morale is at an all-time low both in the military and on the home front. In April 1942, Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle comes up with a daring plan to rebuild morale and bring the fight back to the Japanese Empire: Take 24 B-25 Mitchell land-based medium bombers, load them on the carrier USS Hornet, and launch a symbolic strike of their own on the Japanese homeland. The raid, called the "Doolittle Raid" after Doolittle himself, involves hastily jury-rigging the nearly 10-ton aircraft for carrier takeoffs, alighting from the Hornet, striking various targets in Japan, and landing in Chinese-held air bases for recovery. In practice, the plan goes much more roughly: To start, the sighting of a Japanese picket boat causes the planes to have to launch early, greatly reducing the range of the bombers. While the flight over the mainland goes mostly smoothly, another problem arises when it turns out many of the pre-planned Chinese airfields had been taken by the Japanese, and few of the planes had the fuel to divert to secondary airfields, resulting in a majority of the Mitchells having to crash land or their crews bail out. In the end, 3 American airmen were killed and 8 were captured by the Japanese. The damage itself had no strategic value; the planes were too few and too spread out to have a notifiable effect on the infrastructure, and Japanese propaganda mocked it, calling it the "Do-nothing Raid." However, in reality, both the Japanese public and the government had been shaken to the core, and the illusion of the Japanese home islands being impenetrable to foreign attack had been shattered completely, for the first time in centuries. Due to the Americans concealing the fact that the planes had been launched from a carrier (not that the idea of medium bombers taking off from an aircraft carrier was believable enough anywaysnote , the Japanese military believed the planes had come from either an American island base in the Pacific, or a Chinese airfield. This prompts the China Expeditionary Force to go on a new offensive in the hills of the Hunan and Jiangxi provinces, with the aim of capturing or destroying all airbases within strategic-bombing range of Japan. The operation is a success insofar as the airbases are all cut off or destroyed. But, as usual, the Japanese overstretch their supply lines and are again forced to withdraw. The IJN, on the other hand, began making moves in the Pacific to take any American-held island base that held even a remote chance of housing strategic bombers within range of the homeland, moves that would eventually culminate in the Battle of Midway.

For their part, the Imperial Navy seeks a decisive battle with the U.S. Pacific Fleet, in the hope that its (certain, of course) destruction will buy them a year or two of breathing space (or even, the more optimistic among the Imperial Cabinet hope, a negotiated peace). By this time the U.S. has also committed itself to a "Europe-first" strategy, one that has decided the U.S.'s use of Jiang and the Guomindang—they consider his régime too weak, inefficient and politically unreliable to be trusted with the kind of resources needed to fight Japan on equal terms. The U.S. Navy's argument—that it'd be cheaper simply to prop the Guomindang up with the bare minimum of support necessary and use the Pacific Fleet to "island hop" into a position where they can blockade or even invade the Japanese Home Islands—wins out. For now, however, the U.S. works hard to keep up the appearance of Sino–American solidarity.

When Douglas MacArthur arrives in Australia after escaping the Philippines by PT Boat, it isn't a foregone conclusion that he is physically safe. Just as Malaya's defense is collapsing the Japanese launch an invasion of Rabaul to the far north-east of New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. The Allies can only respond with limited bombing raids, and the Japanese quickly convert Rabaul into a huge military base. They construct airfields, organize supply depots, and expand the natural harbor and port facilities as they build up their forces. Their target is now clear: New Guinea will be invaded next. The last physical obstacle between the Japanese and mainland Australia is set to fall.

Much like Malaya, New Guinea is a mass of high mountains and dense jungles. The city of Port Moresby on its south coast is now the unofficial frontal HQ of the Allied war effort in the South Pacific. All major supplies for the American and Commonwealth war effort passes through it. Fuel, ammunition, food, and air support all are managed from its bases. Port Moresby is relatively defensible since it sits behind a high mountain range, but it doesn't have the naval guns of Singapore (for all the good they ended up doing). Also, the seas around the island are exceedingly dangerous to operate out of. Numerous official Allied and Japanese maps rely on notes from the European explorers of the 1800s to note where dangerous coral reefs and hidden shoals are located. Most are still uncharted and limit their options for naval landings to the few guaranteed safe harbors. More supply ships are sunk by nighttime collisions with these reefs than by enemy fire. MacArthur looks at all of these factors and decides he's had enough of defeat and retreat. After he is installed as overall commander of Allied forces in the Pacific, he makes it clear that Port Moresby will. Not. Fall.

The Japanese depart from Rabaul and land on the northern shores of New Guinea, but their invasion flotilla is mauled by planes launched from New Guinea and the aircraft carriers Yorktown and Lexington. The Allied planes sink three transports and a minesweeper while damaging several destroyers and support ships for the loss of a single fighter craft. But the invasion cannot be stopped and Japanese boots hit the beaches of New Guinea.

Initially the Japanese prepare to launch an ambitious five pronged air/land/sea offensive code-named Operation Mo to take Moresby, but a defeat in the Coral Sea (see below) forces them to call it off and prepare a two-pronged offensive à la Malaya. One offensive group will advance to the east, march the length of New Guinea all the way down the coast, around the enormous peaks of the Owen Stanley Range, and go the same distance on the south side to eventually strike for Port Moresby. The march will be long but they will have the advantage of air cover, roads, and some support from the IJN. The other attack force will try to cross the mountain range, trek through the dense jungles and hills to storm Port Moresby like Hannibal's army crossing of the Alps.

The mountain offensive begins when the Japanese seizing the village of Buna on July 21st, their troops overrunning the single Australian battalion in the town after a week of fighting. MacArthur is presented the option of sending paratroopers to contest the attack but he prefers to fight smarter, not harder—the paratroopers would simply be surrounded and destroyed, and the Japanese were already bearing down on him with multiple divisions. He holds back the paratroopers and bides his time.

Buna sits at the far north-east coast of New Guinea and at the head of what is called the Kokoda Track, the only path through the Owen Stanley Mountain Range. At the far south end of that track is Port Moresby. The Japanese begin fighting down the mountain trail with 13,000 troops, pushing further and further into the jungle hills while the Australians pull back. MacArthur sends 30,000 Australians into the hills to stop them. The fighting seems to be mirroring the campaign for Singapore, with a numerically superior Commonwealth force being overrun and forced back by a smaller Japanese force. Both sides are again plagued by supply problems- lack of heavy weapons and artillerynote , insufficient air covernote , and poor logistics mean this is literal man-to-man fighting. Supplying so many men via a handful of jungle tracks and a single "road" (really just a well walked trail) was simply an impossible task for the Australians. The Japanese have similar problems and the added difficulty that their supplies must travel even farther- the home islands are significantly farther away than Australia. Each soldier is ordered to carry 16 days worth of rations in their pack for a campaign that will last 45 days- but despite empty stomachs and steadily dwindling ammunition, they keep going on the offensive. More Japanese soldiers will die of disease and malnutrition than combat at this stage of the fightingnote .

The Australians choose to solve their supply problem by drafting 16,000 native Papuan plantation workers into the war effort. Some are promised the length of their indentured servitude will be cut, or they'll receive monetary payment, only to find these promises broken after the war. Others are told that the work they would be doing would be significantly easier than the grueling plantation work that was their daily life. Others are drafted at gunpoint. The porters head to supply drop zones in the jungle after Allied planes pass overhead and gather every ounce of food and ammunition they can carry. Backs bent under the strain, now comes the hard part. The Kokoda Track stretches 100 miles from end to end, winding through dense jungles and ascends as high as 7,000 feet- roughly as high as the Appalachians. Again, there are no roads to their destination, only foot paths.The porters take as much as they can physically carry up these tracks through the grueling heat and humidity, all the way to the front lines of a war zone, collapsing from exhaustion, hunger, and disease when they make their deliveries. The Australian medics at the front will write that these porters arrive in worse shape than the Australian war wounded.

And then, many will voluntarily offer to take wounded Australians back down the track- four Papuans to a stretcher, treating the soldiers with considerable care. They build shelters and scavenge food and fresh water for their patients after nightfall and return the wounded to safety at Port Moresby.

And while there is a 30% desertion rate after the porters finish this backbreaking trek, many go back to the drop zones and do it all again.

The Papuan Porters came to be called "Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels"note by the Australians and were recognized for the care they gave to the Aussie troops and their role in winning the campaign... in 2009, long after most of the porters had died.

As the battle continues down the track and the Australians retreat again and again up the slopes and then down them, MacArthur listens to the reports of exhaustion and supply problems and refuses to allow further retreats. Multiple Australian generals are sacked and replaced. Some Aussie troops come close to murdering their commander when he announces at the brigade parade ground that high command believes they aren't putting their all into the fight. The allied lines finally stabilize at Imita Ridge on September 17th and the Australians are finally able to breathe, rest, and reorganize. A special battalion of 500 militia is raised to infiltrate the jungle and hunt Japanese supply columns coming up the tracknote . The Japanese are energized as they take up battle positions near the ridge. They break into the last of their rations to celebrate. The officers share sake toasts to their success. They're now about 60 kilometers from their target. At night they can see the lights of Port Moresby. But these celebrations can't stop the painful stabbing sensations in their empty stomachs or reload their rifles. While they are still waiting for resupply, the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels are bringing more bullets, bandages, and bombs to their Australian foes every day. The Japanese commanders have to make an impossible decision.

Australian Brigadier General Eather prepares his troops for a massive, all out offensive and launches it on September 27th- only to find the Japanese positions empty. The Japanese, weakened from hunger and disease, could not continue down the track and had withdrawn, heading back to rejoin their supply lines. The Australians launch a pursuit and within a month have chased the Japanese back down the track to the village of Buna and hold the Kokoda track uncontested.

Simultaneously with the Kokoda Track campaign, MacArthur receives word from Allied cryptographers that the Japanese will try to seize his airfields at Milne Bay on the far eastern hook of New Guinea as part of their long eastern march. The airfield is a front line facility that can launch air attacks against Japanese ships in the Coral, Solomon, and Bismarck Seas. If it's shut down, the IJN can conceivably hit the Australian coast without aerial interference. But the Japanese Army is starting to feel overstretched at this point and insists they can't provide any troops to help in another naval landing, so the IJN agrees to send 1,500 men from the Kaigen Rigusentainote to capture Milne Bay. The Japanese think they are going to attack an airbase with at most 600 men- most of them staff and air base personnel. MacArthur is waiting on the beach with a force of 9,000 men- local militia, Australian regulars, and American engineers and artillerists. The Japanese still put up a heavy fight and with help from a bad weather front that keeps Allied planes grounded, and an IJN cruiser squadron's heavy guns, they are able to break through the beach defenses with 1,000 marines and both of their tanksnote . The fighting continues for two weeks but the battle becomes a wash and a retreat is called by the Japanese- they actually have to leave several companies stranded on a nearby island until they can be picked up in October by a submarine and a light cruiser. MacArthur orders the base to be significantly expanded and used to pound the Japanese all across New Guinea, stopping the slow-and-steady offensive before it can reach the airfield.

The Japanese make one final push for New Guinea in 1943, setting their sites on the village of Wau. An inland town within reasonable striking distance from the shoreline, Japanese commanders learn that Wau has a functional and lightly staffed airfield- it had been built during a gold rush in the 1920s that hadn't quite panned out. The Japanese gamble on taking this base and using it for an airborne resupply operation, and then as a stepping stone for a strike at Port Moresby. The survivors of the Kokoda Track Campaign regroup to make a push on the airfield. By all accounts, the numerically superior Japanese should have overrun the Australian defenders- but the Aussies hold and repel the assault.

With Guadalcanal collapsing, Japanese High Command decides they absolutely need to take Wau to regain the strategic initiative in the Pacific. They gather the 51st Imperial Division in Rabaul and have them board eight transport ships as a reinforcement flotilla. The plan is to move the vulnerable convoy behind a bad weather front as a shield against allied aircraft. And even if the flotilla is discovered by the Allies, High Command is fully prepared to lose ''half'' of their troops just getting to New Guinea. About 7,000 Japanese troops escorted by a convoy of destroyers and submarines leave safe waters on February 27th. What follows is nothing short of a massacre. Allied intelligence had again broken the codes of the Japanese and detected the buildup of troops. MacArthur has his air teams outfit their bombing craftnote with no less than 8 nose mounted .50 caliber machine gunsnote in preparation. The bad weather shield works for the Japanese at first, but it dissipates by March 1st and then everything gets FUBAR. The convoy is spotted by an allied scout plane and a force of bombers and PT boats descends on the ships. Even with Japanese air cover, the Allies sink every one of the transport ships and 4 of the destroyers. Almost 3,000 Japanese troops sink to the bottom of the ocean. The rest are fished aboard the surviving destroyers and submarines in the night. About 1,000 men make it to New Guinea but were in no condition to begin a march to Wau. The rest return to Japanese ports aboard the destroyers.

The fight for New Guinea would continue until the war's end. The Japanese had committed 300,000 men to the task, and while over a third would die of disease or starvation, the fighting didn't stop. But it was a foregone conclusion after the attempts for Wau. Australia was safe and they along with MacArthur had bought time to re-orient Allied strategy after the disasters at Singapore and Pearl Harbor. From here the American and Australian strategies split. The Aussies and Dutch launched a westward advance into Western New Guinea and the Dutch East Indies, while MacArthur and the Americans prepared to return to the Philippines.

The Pacific War is an island war, something the world had never seen before and has never seen since. It is a long-distance war, waged largely by air and sea power, but mostly it is a struggle for island bases that have no strategic value other than as stepping stones that can be used to carry the war to the enemy. Most have no useful resources and their tiny native populations are either neutral or indifferent to the titanic clash surrounding them. Only the largest archipelagos like the Philippines and Indonesia have resources worth fighting over and populations with vested interests in the outcome. Unlike a land war, island bases can easily be cut off from their supply lines, effectively making their entire garrisons prisoners of war without an actual fightnote . In this environment, relatively small battles and conquests can carry huge strategic implications, and the tactical character of the fighting is unrelentingly heavy.

Because the battlefields and numbers of troops are so small and the troop concentrations so uncomfortably high, there just isn't the room or the numbers for there to be "exploitation" or even "breakthrough" phases to the fighting—it's all assault-type combat until the enemy's resistance shatters completely. Since no reinforcements can be shuttled in for a counterattack or to reinforce the threatened sector—and the defenders can't retreat to regroup and avoid fighting while they're still disorganized (as in a "breakthrough" phase)—the defenders are then massacred in some very one-sided fighting and the whole battle is over in short order. It's also a form of warfare practically tailor-made for the Americans; with their massive glut of resources (and more efficient management of said greater resources), they can practically create or capture island bases and airfields faster than the Japanese can destroy themnote .

The IJN's superiority in carrier, cruiser and destroyer tactics give them a near-unbroken string of naval victories until mid-1942, as Admiral Yamamoto had warned would happen. Then, at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, the USN engages two IJN carriers. Although suffering serious losses, the USN forces the IJN to turn back from Port Moresby and removes the threat to Australian–U.S. shipping lanes. This turns out to be more significant than anyone could imagine, as damage to two IJN carriers prevents their inclusion in the coming Battle of Midway while the famed American superiority in damage control enables the stricken carrier USS Yorktown to be back in action far sooner than anyone, especially the Japanese, expectednote .

The "decisive battle" Yamamoto hoped for involved a complex operation to invade the island of Midway (plus some Alaskan islands the IJN thought to be more strategically significant than they really were) in June 1942, to force the USN to send its carriers to a fight to the death. But unfortunately for the IJN, American codebreakers have managed to crack Japan's primary naval encryption and have a very good idea of what to expect, especially when they trick the Japanese into confirming their target.note Midway thus becomes a trap for the IJN, turning what could have been Yamamoto's crowning achievement into a series of setbacks and failed objectives that costs the IJN dearly; the Japanese carriers arrive at a forewarned and heavily defended island and aren't even aware of the opposing U.S. carriers until long after the U.S. attack forces have launched. Again, the USN suffers tremendous losses, but they manage to organize a counterattack, consisting of a two-pronged strike of dive bombers and torpedo bombers. The torpedo bomber strikes are disasters; the outdated, slow TBD Devastators are fodder for Japanese fighters and AA guns, especially when they are forced to fly even slower and in straight, predictable lines while lining up for their torpedo runs against the carriers. Compounding this was the abysmal reliability of American torpedoes for the time meaning that the few Devastators that got through and managed to release could only watch as the torpedoes either missed or simply bounced harmlessly off the hulls of the carriers without doing damage. All in all, few if any critical hits were scored by American torpedoes against the Japanese carriers. Conversely, the dive bombers had much better luck: The Japanese fighters and gunners had been concentrating on the low-altitude torpedo planes, and had failed to take into account the SBD Dauntless dive bombers coming in from on highnote . The American Dauntlesses could not have arrived at a worse time for the IJN, as its next strike force was being refueled and rearmed, meaning the hangars of each ship are covered with fuel, munitions and aircraft. The U.S. Navy fatally damages three Japanese carriers in the span of five minutes, and a fourth a few hours later (all would be scuttled within 24 hours), for the loss of one of their own, in an action termed "the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare" by historian John Keegan. Another blow that was dealt was not to a specific nation, but to a method of naval warfare itself: The Battle of Midway had been fought, and won, almost completely by naval and land-based aircraft, with no American or Japanese warship trading cannon fire. It served as visual proof that battleships were quickly becoming obsolete in the face of constantly-improving aviation and ordinance technology, and a clear sign that the time of the great iron monoliths lining up to exchange broadsides was quickly coming to an end.

The IJN isn't destroyed per se, but the blow is a Game Changer. Now fielding two fleet carriers and five light carriers (only two of which were particularly suitable for fleet operations against enemy carriers), the IJN suddenly finds its substantial superiority in naval airpower over the USN's carrier force (three in the Pacific and one in the Atlantic) reduced to mere parity. American industrial production made this inevitable, but the IJN hoped to delay this parity for a good 6-12 months more. Nor will this parity last much longer, because the Americans already have seven new carriers under construction, the Japanese just one, and the Americans are not going to settle for a mere seven to one advantagenote .

Of course, all of this information stays confined to the top brass of the IJN; the official tally of the battle was one Japanese carrier lost with the Americans totally defeated. To maintain the propaganda, thousands of Japanese sailors are quarantined and quietly moved into South Pacific bases without any opportunity to see their families. Mid-level naval officers begin to realize around this time they were not on the winning side—not because they had suffered a defeat, but because the IJN was so politically fragile it could not risk the Japanese people knowing it had suffered even a single defeat. This fragility had already been hinted at in the aftermath of the Doolittle raid—despite the Imperial Japanese propaganda machine doing its damnedest to dismiss the raid as strategically ineffective, it had broken the illusion that the Japanese Home Islands would remain impervious to direct attack during this war, note and this was a rather disturbing fact to Japanese civilians, who culturally held all but but the highest reverence for their government and the Emperor, who may as well be God Himself in the eyes of his imperial subjects given how much deference he commanded; for the Emperor to all but guarantee that Japan would decisively win this war, only to be almost instantly proven wrong by such a direct attack on the Japanese Homeland as the Doolittle Raid, scared the shit out of a lot of Japanese people, so one can only imagine the hysteria which would result from finding out just how badly the IJN had lost Midway.

For the next six months, the IJN and the allies fight a brutal land, sea and air battle for the uncompleted Japanese airbase on the island of Guadalcanal. This would expand into the fight for control of the entire Solomon Islands chain, lasting until November 1943. Much of the momentum of the southern offensive is lost due to the unanticipated effect of partisan and guerrilla resistance, particularly in the Philippines, while the Guadalcanal campaign turns into a six-month meat grinder of horrific foot-slogging battles and fierce nighttime naval engagements that consumes ships, airplanes and men Japan can ill afford to lose and lacks the resources to replace. Another issue the Japanese faced was that their armies were woefully outclassed in terms of equipment: Most Japanese soldiers sported the Arisaka rifle, a tried-and-true but slow firing bolt-action infantry rifle with a capacity of just five rounds, fed by stripper clip. Conversely, American infantrymen had the M1 Garand, a newer and more mechanically complicated design, but capable of a much higher rate of fire and fed by an eight round en-bloc clipnote . Additionally, in an interesting inversion of its weaknesses on the European Front, where it struggled against the heavier-armed and armored German Tiger and Panther tanks, the Sherman tank actually enjoyed a comfortable advantage over Japanese armor, which were both too lightly armed to penetrate the Sherman from the front, and too lightly armored to deflect the Sherman's 75mm cannonsnote . Even then, however, the Japanese forces on Guadalcanal continue to be a serious threat to the airfield—now named "Henderson Field" by its new owners—and surrounding forces; artillery concealed in the jungle and caves on the nearby mountainside take every opportunity to rain shells upon Henderson Field, disrupting airfield operations and generally making life hard for the occupants, and it wouldn't be until February 1943 that the Guadalcanal Campaign would be officially concluded.

The IJN's Mobile Force, now reduced to two large fleet carriers and whatever light/escort carriers and other conversions it could muster after the disastrous Battle of Midway, nonetheless made a good showing at the Battle of the Eastern Solomons in August 1942, and the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands in October 1942, managing to severely damage the USS Enterpise in the first battle despite being forced to withdraw and then forcing the American Navy to retreat in the second. By the end of the year, Japan had even succeeded in its objective of neutralizing the U.S. carriers—air and submarine attacks had sunk 4 of the U.S.'s 6 large fleet carriers, leaving only the badly damaged Saratoga and Enterprise. However, the Japanese were in no condition to exploit this turn of events, as the loss of aircraft (worsened by the low survivability of their fighters and lack of effort in rescuing their own downed pilots) meant a full half of their Pearl Harbor aircrew had already perished. By the end of 1942, with both U.S. and Japanese carrier forces having worn each other down to nubs, both sides retired to repair and rebuild their carriers and air wings. It would be another 18 months before the U.S. and Japanese carrier fleets engaged each othernote . Making matters worse for the Japanese Navy is the fact that their pilot training & retention doctrine was starting to become a major problem. Japanese Pilot Training was incredibly selective and rigorous that led to some of the best pilots in the world, but they were also kept on-duty & in front-line service indefinitely (typically until they were killed). This approach meant that over time Japan began to lose its vital pilots but could not replace them, made worse by the fact that (unlike other nations' programs) Japanese Aces were never sent to aviation schools to share their expertise & knowledge with the next generation of pilots, which only exacerbated the drop in quality of pilots as the war continued. Adding insult-to-injury, the Japanese Navy also failed to implement a policy to rescue their downed pilots who survived crashing their planes into the ocean; pilots were only rescued if they just-so-happened to crash near a Japanese ship, otherwise (unlike the Americans who regularly sent patrol seaplanes to rescue downed airmen in the ocean) a skilled pilot was permanently lost in the vast Pacific Ocean with no prospect of survival, much less rescue.

With the Solomons secured in late 1943, U.S. and Australian forces will go on to liberate the rest of New Guinea together and then part company, the Australians driving west into Indonesia while the U.S. turned north towards the Philippinesnote . The vital Japanese naval bases at Rabaul and Truk are attacked by the USN in late 1943 and early 1944, respectively; the Japanese Navy is forced to abandon its southernmost defensive lines and retreat to the Marianas.

The Imperial Army's advances into Burma showcase some serious issues with the tentative Sino–British–American alliance. For one thing, Stilwell immediately overrides his commanders' objectionsnote . He orders his on-loan Guomindang divisions to drive back the Japanese offensive by way of a counterattack—even though his forces are outnumbered three to one, lack communication equipment, have no air cover, air support, or artillery, and are not supported by their British allies (who think it's a spectacularly stupid idea). It fails, and Jiang goes over Stilwell's head to order his encircled forces to make a breakout and retreat. The Japanese advance soon cuts off the Burma road, China's sole remaining transport link to the rest of the Allies-aligned world. Its loss forces the Americans to fly everything from Bazookas to bandages over "the Hump" of the Himalayas in order to meet their Lend-Lease commitments.

As Guomindang troops and the Sepoys of the British Indian Army bring the offensive to a halt in the Himalayan foothills, Gandhi and the Indian National Congress declare the start of the Quit India movement—which advocates Britain's immediate withdrawal from India to make room for Indian independence. Gandhi and the Congress are promptly imprisoned for the duration of the war, and acts of open rebellion and sabotage are quite brutally suppressed. However, Jinnah and the Indian Muslim League declare their loyalty to the British Raj and give the war effort their full support—their proposal of an independent or autonomous Indian-Muslim State (aka the modern nation of Pakistan) is taken seriously as a consequence.

Like the Chinese, the Anglo–Indian army is a bit short on equipment and weaponry (though nowhere near as badly), and this is where the Americans come in again. Jiang keeps Stilwell on as commander of his stranded forces, despite his incompetence. Jiang can hardly ask for his troops back now, as that would be politically awkward, and besides, Stilwell is useful because he is pretty much the only U.S. commander who demands that Jiang be given any measure of Lend-Lease material and support. Moreover, Jiang doesn't trust the British not to use his troops like they do the Sepoys: in the defense of their Empire rather than China. Thus, Stilwell sees to it that the U.S. Army educates, trains and equips Jiang's forces to its own standards—though the U.S. Army keeps them on the wrong side of the Himalayas. U.S. forces begin to hop in earnest from strategically-important island to island, avoiding fighting nonessential battles and winning each one. However, this comes at what the Americans consider frightful costs in the face of China-veteran garrisons, who fight almost literally to the last man rather than surrender. The war in the eastern Pacific quickly comes to mirror that in the west—the mutual, deep-seated (and oftentimes racial) hatred and animosity on virtually all sides means that quarter is rarely asked or given.

At least, this is the plan presented to the Emperor; the real plan is far more realistic, which speaks volumes. The Army is confident only in its ability to take the mid-Yangtze, linking up the railways from Beijing down to Guangzhou and capturing or rendering unsafe the forward airbases Chennault's air forces are operating from in the process. Mindful of his forces' deterioration and the inevitability of Allied victory, Jiang had been highly critical of Marshall's decision to give Chennault forces enough to antagonize the Japanese into making a grand offensive—at least, not without giving his troops the weapons, training and equipment needed for them to hold off such an offensive. Chennault actually has half as many planes as the Imperial Army does in China now. This is a serious problem for the Empire given the huge amounts of territory and the number of strategic fire-bombing missions they have to defendnote . The result has been chaos in the occupied territories as Japan has neither sufficient radar installations, antiaircraft artillery, or planes to defend their lines of communication and supply properly. Thus, Operation Ichigo is the solution.

It's worth noting that even if Ichigo does succeed beyond High Command's wildest dreams, Japan will still lose the war. It's only a matter of time before the U.S. Navy manages to blockade and perhaps even invade Japan itself. Furthermore, the American air forces are only a couple of islands and a few months away from being able to launch strategic bombing raids on the Home Islands themselves. High Command can hardly claim ignorance of the offensive's futility, as their other big project is wrangling out a defense plan for the Home Islands with the cooperation of the Navy, but they go ahead with it anyway.

Initially, Ichigo seems like a wild success. The Guomindang's Henan salient—which has to be supplied by oxcart, as the Japanese hold the railway network at either end of it—is eliminated in mere months after having held out for seven years. Changsha is captured, again. The Japanese hold onto it this time as they regroup and then concentrate virtually all their artillery and armoured forces to take the Guangzhou-Changsha railroad, fanning out into the mountains to take out the Allied airbases from there. Jiang tries to get his forces recalled from Burma, but Stilwell refuses, as Marshall has told him that Jiang doesn't need them. Stilwell, moreover, has been trying to get Jiang to commit more troops to help out in the Allied offensive in Burma. To do so, he has been withholding Lend-Lease supplies for months, such that even Chennault (with whom he has a very thorny relationship) is short on spare parts and fuel, and complains about Stilwell's conduct to Marshall.

Worse still, when Chennault tries to use his planes to disrupt the Japanese offensive, Marshall tells him to pull his forces back to Chongqing and reduce his operations—though U.S. high command initially didn't realize the scale of the offensive, they soon come to believe that it might mean the end of the Guomindang. Roosevelt soon looks to cut his losses in the runup to the U.S. election of November 1944. Roosevelt's opponent, Thomas Dewey, relentlessly criticizes Roosevelt's conduct of the war and lambastes him for not providing Jiang with enough support. By way of response, Roosevelt allows the publication of a series of previously-censored articles which are highly critical of Jiang, the Guomindang, and their forces. If China loses, Roosevelt says, it will be their own fault—and Marshall will ensure the USA's losses will have been minimal. Jiang, accordingly, is absolutely furious but has to bite his tongue, insisting only on the resumption of Lend-Lease deliveries and the dismissal of Stilwell.

Then a doomed-to-failure offensive directed at capturing Chongqing is launched by a faction of rogue Japanese generals. It not only fails, it goes on to backfire spectacularly as the Guomindang's opportunistic counterattack turns into a counteroffensive precipitated by success upon success at the tactical level. This actually forces the Japanese to retreat and abandon their precious Wuhan-Guangzhou railroad as the Guomindang re-capture Changsha. Not at all coincidentally, the Burmese front is also moving again after years of stalemate. The long-planned Sino–Anglo–Indian offensive, something Jiang has been pressuring the Americans and British to get around to for years now, gets off to a shaky start as organizational issues come to a head.

But after their resounding victory at Imphal, the Allies' mechanized forces lead a mad dash to capture as many Japanese troops as possible and get to Rangoon before the monsoon season starts and bogs down the offensive for another few months. Racing from just-captured and barely-serviceable airfield to barely-serviceable and barely-secure airfield, getting virtually all their supplies by airplane because of the god-awful roads, a last-minute amphibious operationnote takes Rangoon just days before the monsoon hits. Most of Japan's Burma force is out in the open, but the British are unable to follow up on this and push into Japanese-allied Thailand until the monsoon season ends and the floodwaters recede.

In the Pacific, the year 1944 is turning out very poorly for the IJN. Powerful USN amphibious forces, backed by massed carrier-borne airpower, have already wrested control of most of the Solomon Islands from them, and Japanese bases throughout the Gilbert and Marshall Islands are rapidly collapsing as the USN drives north faster than the IJN can effectively reposition its defensive lines. The major Japanese base of Rabaul has been surrounded and rendered impotent by relentless air attack from Henderson Field and constant submarine presence- MacArthur is content to starve the Japanese out in a siege rather than give their soldiers a death in battlenote . Anticipating an imminent attack on its major fleet base at Truk, the IJN pulls the Combined Fleet closer to the Home Islands. This is wise, as in February 1944, a massive USN force of eight (!) aircraft carriers launches thousands of sorties on Truk over the course of several days, stopping only when nothing was left afloat, few aircraft still flyable, and no significant structures left standing. IJN leadership expected an attack but is stunned by how effortlessly their main Pacific base was reduced to ash.

As the USN push northward into the Marianas Islands, the IJN is spurred to action: if the U.S. builds airfields in the Marianas, the Home Islands will be at serious risk of long-range American bombers. In June 1944, Admiral Ozawa sails forth with the newly-reconstituted Mobile Force, aiming to draw the American fleet into range of its naval airbases in the Marianas and use combined land-based and carrier-based aircraft to overwhelm the U.S.'s fleet, in what would be known as the Battle of the Philippine Sea. In a sign of how desperate the situation is, the IJN ships are fueled with raw, unrefined crude oil. They'll make it to the battlefield and back but at the end, the engines and boilers of the entire Home Fleet will be completely ruined. But if the IJN can score their own Midway-style decisive victory, they may have options for negotiating an end to the war or just building new engine components for the fleet.

Unfortunately, by the time Japan decides to recall its top carrier pilots from their stations in South Pacific bases, most are already dead and the rest have been worked to the point of physical and mental breakdown in 24 months of nonstop heavy combat. Further, the USN fully appreciates the trap and wipe out all Japanese airpower in the vicinity days before Ozawa arrives. The USN sets up a deep defense of warships sporting the new proximity fuse shells and radar-directed fighters, which not a single Japanese aircraft penetrates. Attacks by U.S. aircraft and submarines claim three precious Japanese aircraft carriers, while the worst the Americans get is frustration over the other six getting away (half of which were damaged and all were severely deprived of usable planes, but still). IJN leadership suffers yet another shock: it had taken extraordinary resources, spread out over two full years, to get that many ships and aircraft and trained aviators together into the refurbished Mobile Force, and the Americans had sent all of these things to the bottom of the sea in the space of an afternoon. The IJN knew now their carrier forces were finished; their front-line carrier wings were annihilated and simply could not be replenished. The battle comes to be known in the U.S. as the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot"note .