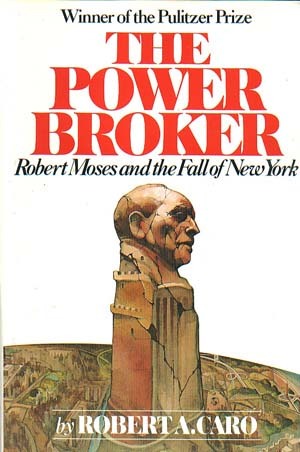

The master builder.

"Some men aren't satisfied unless they have caviar. Moses would have been happy with a ham sandwich—and power."

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York is a biography by author Robert Caro of New York's "master builder" Robert Moses, published in 1974. Moses was responsible in some way for hundreds of highways, parks, bridges, and other public works in New York City and State, including Lincoln Center, the Triborough Bridge, and the United Nations. The book also includes a whole lot of history of 20th-century New York during Moses' upbringing and period in power.

The Power Broker contains examples of:

- All Your Base Are Belong to Us: The bloodless merger of the Triborough Bridge Authority, Moses' last power base, into the MTA (see under Hoist by His Own Petard, below) by Nelson Rockefeller.

- Almighty Janitor: For fourteen years, Moses worked in government without drawing a salary.note He never got an elected position. Even at the height of his power, he was technically just an appointed parks commissioner (plus a few other titles). But his actual power was way out of proportion to how his titles sounded.

- Anti-Hero: Whatever crafty ways Moses found to fund or implement his projects, particularly in his early career, he nevertheless delivered the parks, roads and bridges city politicians had promised for decades, making him extremely popular, especially since they often benefited the masses at the expense of the idle rich of the era.

- Badass Bureaucrat: Early in the book, Moses is called "the best bill drafter in Albany." Caro repeatedly calls back to that description as Moses cuts through the rest of the bureaucracy over and over, using cleverness, aggressive tactics, and intricate knowledge of the law. A few times, he embeds secret loopholes in legislation and manages to give himself serious power before anyone can notice.

- Berserk Button: Any mention of Eleanor Roosevelt, apparently. Moses already had had a difficult relationship with her husband when he was governor, and when a newspaper column she wrote led, ultimately, to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel being built instead of the bridge Moses wanted, one of the few defeats he suffered in his earlier career, he never forgave her. As late as the 1960s, his acquaintances say that in private, whenever her name was mentioned, he'd go on angry rants, often (they implied) referencing her sexuality.

- Big Apple Sauce: As in real life. Plus Long Island and some of upstate New York.

- Cain and Abel: Robert and Paul Moses.

- The Chessmaster: Caro quotes one politician as saying that Moses knew not only just exactly who to put pressure on, but exactly how much. He never asked them to do something they couldn't plausibly do.

- Corrupt Politician: Lots ... flamboyant 1920s mayor Jimmy Walker, the upstate gang of legislators known as the Black Horse Cavalry, the Bronx officials whose secret interest in a local bus company requires that the Cross Bronx Expressway be built on a harder route that destroys a neighborhood so as to preserve the bus depot. Moses learned to work with or around them to get his projects built, as the situation demanded.

- Deathbed Confession: Averted. Paul Moses was going to finally tell Caro just what it was that had so alienated him from Robert, and indeed the rest of the family, but shortly before the interview he suffered what turned out to be a fatal heart attack and never regained consciousness.

- Determinator: Moses never gave up on his early projects, always finding a way around some financial, political, legal or engineering obstacle.

- Did You Just Flip Off Cthulhu?: At one point an unnamed Republican legislator in Albany recounts how, one day in the early 1950s, he walked past Moses's open office to hear him engaged in a Cluster F-Bomb rant against a "Tom" on the other end of the phone before hanging up.

- "Bob, was that the governor?"note"Yeah", Moses replied, grinning with satisfaction.

- Subverted in that Moses really did have more power at the time than the state's highest elected official.

- Doorstopper: The book is 1344 pages long. And Caro's final draft was actually much longer, but his editor made him shorten it so it could be published in one volume.

- Establishing Character Moment: Caro opens with a scene from Moses's days at Yale near the beginning of the 20th century where, after being confronted by a swim teammate about a dishonest plan of Moses's to raise money from a donor, he resigns in protest and never swims for Yale again.

- It is juxtaposed with a similar scene from the 1950s when, after newly sworn-in Mayor Robert Wagner fulfills a campaign promise to his reform-minded supporters and declines to reappoint Moses to the city's Planning Commission. Observers note the scene and see that Moses is threatening to resign, as he has in similar situations in the past. Moses simply follows Wagner into his office after the ceremony, rips out a blank appointment form and fills in his own name and "Planning Commission", then, without a word, hands it to Wagner, who promptly signs it. By that point Moses had so much power that mayors and governors needed him far more than he needed them; his threat to resign often did not need to be stated aloud.

- A Father to His Men: At first, Moses is this to his staff (engineers, architects, planners, and so on). Caro says he had a gift for finding capable people, and they become the "Moses Men" who run his empire. But over time, Moses' appointees become less and less competent.

- He Who Fights Monsters: Moses was a Progressive-era reformer in his early career, fighting the patronage and corruption of the city's Tammany Hall political machine. While he failed in many of those efforts, the good graces he won served him well in the publicity department well after he had started resorting to whatever underhanded tricks he could to get what he wanted.

- Hoist by His Own Petard: By the late 1960s, Moses was down to running only the Triborough Bridge Authority, which (its name notwithstanding) operated all the toll bridges and tunnels within New York City limits. There had come unto Albany a governor who was not politically dependent on Moses, who came from a family with its own vast wealth: Nelson Rockefeller. While he worked well with Moses initially and shared similar political skills, he slowly reduced Moses's influence. A few years after edging Moses out of his seat on the State Parks Commission, his last significant state-level job, Rocky decided that all of the city's public-transit agencies, including Triborough, should be consolidated into what is today the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

- Moses could have blocked this via the Loophole Abuse noted below, since this would have amounted to an alteration of the bond contracts. But ... those same contracts also designated an agent to act on behalf of the bondholders in the litigation that would have been necessary. Who was that agent in this case? The Chase Manhattan Bank, run at the time by ... the governor's brother David. Thus the deadline for Triborough's merger passed with Moses being able to do nothing more than complain about his final loss of power.

- Honor Before Reason: Moses' criticism of the more idealistic reformers in the city.

- Informed Judaism: Invoked by some of his Jewish critics. His family was Jewish, but not very observant, and Moses became even less so as an adult, eventually getting very close to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of new York (a good political ally) and its leadership, presaging his conversion to that faith late in his life.note

- Irrational Hatred: Even some of Moses' closest associates couldn't deny that he had it in for African Americans. He went to great lengths to discriminate:

- He built many swimming pools in parks all over New York ... but none in Harlem, and he always required that pool water be kept below a certain temperature in the belief that blacks wouldn't want to swim in water that cold.

- He was instrumental in converting much of the Hudson River shoreline into parkland ... but avoided doing so in Harlem.

- He supposedly insisted that bridges on the parkways he built be low enough that buses couldn't get under them, the better to keep the sort of people who primarily traveled that way off them and out of his parks. (Although, this one may not be true.

)

) - He made sure the subway was starved of city cash (until the mid-60s, it was privately run) so it would be an unreliable way to go from black neighborhoods to city beaches at Coney Island.

- Jerkass Has a Point: While the fight to build the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel rather than the bridge Moses wanted (see Berserk Button, above) was largely a turf war, Moses made the correct argument that it is much easier and cheaper to expand a bridge's traffic capacity than a tunnel's.

- Left Hanging: Caro never found out what the issue between Paul Moses and the rest of the family was. As noted above, Paul died before he could say, and when he asked Robert, Moses stopped cooperating with Caro on the spot.

- Loophole Abuse: When he was picked to head up the public authorities whose primary purpose was to borrow money to build roads or bridges, collect tolls to pay off the debt and then dissolve after transferring the infrastructure to the state, Moses realized that if he wrote the bond contracts for the debt to include the legislation authorizing the authority's existence by reference, the contracts would be politically unbreakable since the U.S. Constitution forbids state legislatures from changing the terms of existing contracts. And there was no law saying the authorities, once created, couldn't continue borrowing money. Both of these provisions were exploited by Moses to keep himself in charge of these authorities and the tolls they collected far longer than legislators originally intended.

- The legislation creating those authorities also allowed, in many cases, for the authority to build or have a hand in building any other project which might affect traffic on the roads or bridges. Moses took advantage of this to build parks (in one case on either side of a road he had built) and housing projects.

-

Magnificent Bastard: Moses practically defines this. Half of the book is about the long string of ingenious tricks he uses to manipulate the system into letting him do anything he wants.

Magnificent Bastard: Moses practically defines this. Half of the book is about the long string of ingenious tricks he uses to manipulate the system into letting him do anything he wants. - Mentor Archetype: Al Smith, New York's governor in the 1920s and the 1928 Democratic presidential candidate. He gave Moses his first job in state government—as New York's Secretary of State—and taught Moses a lot about how the game was really played. For the rest of Smith's life Moses never forgot him, going so far as to have a special key made for him so Smith could go visit the Central Park Zoo whenever he wanted.

- Outside-Context Problem: Rockefeller, since his family's immense wealthnote gave him a political power base that made him impervious to Moses's influence.

- Parental Favoritism: Moses and his mother Bella. Comes to a head when she dies and Paul is mostly cut out of her will, something Caro suggests Moses might have had a large hand in since he was in a difficult financial position at the time.

- Red Scare: During the 1950s Moses took advantage of the McCarthyist political climate to suggest his opponents were Communists or useful idiots.

- Screw the Rules, I Make Them!: Sort of invoked by how Moses, in his later years, would sometimes, for fun, let some young lawyer at one of the agencies he ran go on about whatever relevant law was at issue, then stop the man by saying "I know the law, young man ... I wrote it", which he actually had.

- Actually what he had done was sort of invert the trope ... he wrote the rules so well he would never have to actually say, in so many words, "screw the rules" to do as he wanted.

- Screw This, I'm Outta Here: Averted many times after being played straight in the opening scene at Yale. Moses' favorite tactic when confronted with an elected official with power to oppose him was to threaten to resign from one or even all of the jobs he held; it always worked as none of them wanted to have to explain why they forced such a popular and competent official out of his job.

- Sliding Scale of Idealism Versus Cynicism: Moses moves from extreme idealist to extreme cynic.

- Suddenly Significant Rule: Moses drafted the bill that authorized the construction of the Northern State Parkway to give him the power to use a never-used state law to acquire land, one that allowed him to basically just walk on the land and take it.note

- Suburbia: The parkways Moses built so that the increasing amount of city dwellers with automobiles could get to the state parks he built on Long Island help turn Nassau County from potato-farming country into today's suburban sprawl after World War II.

- Urban Segregation: Caro blames Moses's racism and his projects for increasing the city's racial segregation.

- Utopia Justifies the Means: Lampshaded by Moses's own line, recalled by a number of his subordinates: "If the end doesn't justify the means, nothing does."

- Villain Protagonist: In Caro's telling, Moses becomes increasingly villainous and interested in power for its own sake as the decades pass.

- What the Hell, Hero?: Judge Samuel Seabury, a legendary anti-corruption fighter, calls Moses out for basically becoming what he once opposed at a party in the early 1930s, when Moses still enjoyed a very favorable reputation.